Post written by Mason Vander Lugt. This is the fourth and final installment in a series about the development of the recording industry in the 1890s. The first, second and third provide additional context.

The first cracks in North American’s monopoly of American record sales began in spring 1893 when Victor Emerson of the New Jersey Phonograph Company formed an independent agency called the United States Phonograph Company. The sub-companies had been authorized to sell phonographs, but only within their respective territories. The United States Phonograph Company, on the other hand, could purchase phonographs from the New Jersey Phonograph Company (presumably at cost) and resell them anywhere, not having signed any exclusive agreement. Leon Douglass of the Chicago Central Phonograph Company organized the Chicago Talking Machine Company under the same principle, around the same time[1].

Both companies had access to duplication technology that gave them an advantage in the coming years. Both also predicted the direction of the market and invested in spring-motors for home phonographs – Frank Capps’ for United States and Edward Amet’s for Chicago. From the beginning, United States had the expertise and connections to record the industry’s established stars. An impressive USPC catalog in the New York Public Library shows that they recorded many artists made popular by the North American sub-companies. Chicago recorded local artists like Silas Leachman and Bonnell’s Orchestra, but also courted visits from the popular eastern stars and distributed records taken by the other companies.

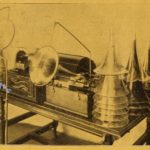

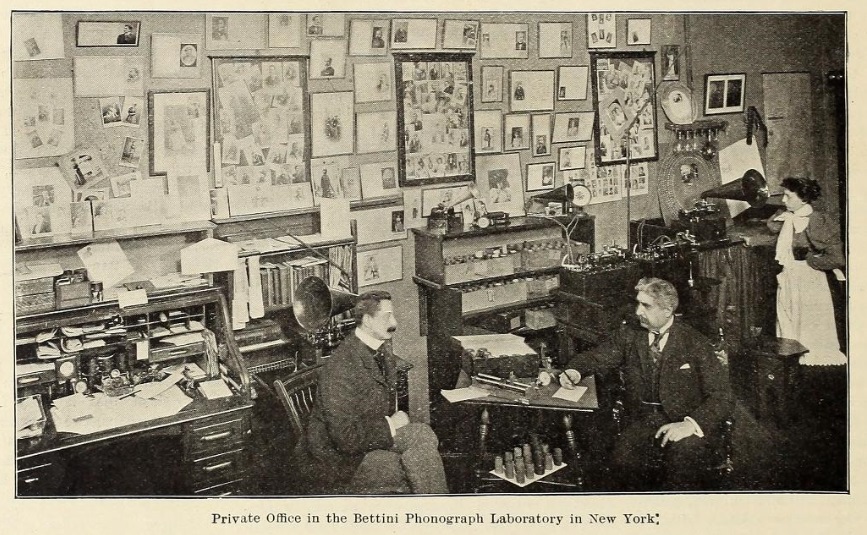

Meanwhile in New York City, an Italian inventor named Gianni Bettini used his social connections and technical reputation to record the stars of opera. Bettini’s involvement in the industry began with inventing high-fidelity recording and reproducing devices in 1889, but by 1892 he had begun recording on a small scale, and by 1896 was one of seven producers listed in Phonoscope’s “New Records for Talking Machines”. Like the United States and Chicago companies, Bettini held a patent on a duplication process, and would distribute copies of his original records, first through the New York Phonograph Company, then through his increasingly prestigious 5th Avenue Phonograph Laboratory.

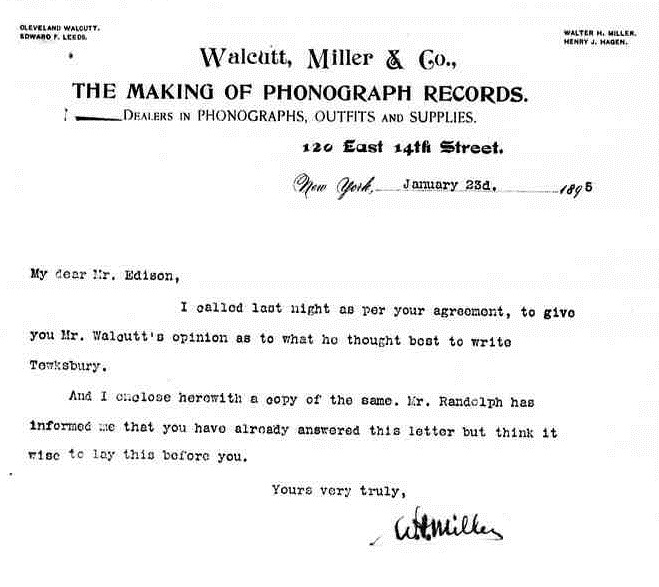

After North American collapsed in August 1894, a group of industry elites assembled who would in various forms guide the industry through the decade. The initial organization, Walcutt, Miller & Co., was founded by North American secretary Cleveland Walcutt, Edison recording manager Walter Miller, Edison recordist Henry Hagen, and Edward Leeds, who independently leased phonographs in Indiana. The coalition bought North American’s 14th St. recording laboratory and equipment.

A January 1895 letter in the Edison Papers suggests Walcutt, Miller & Co. intended to work with Edison to assert Edison’s exclusive right to record manufacture against USPC, which George Tewksbury had since joined.

A January 1895 letter in the Edison Papers suggests Walcutt, Miller & Co. intended to work with Edison to assert Edison’s exclusive right to record manufacture against USPC, which George Tewksbury had since joined.

This partnership lasted until February 1896 when Miller and Hagen formed the Phonograph Record and Supply Company and Walcutt and Leeds went their own way under that name. Walcutt and Leeds developed a major recording operation before falling to one of American Graphophone’s many lawsuits in July 1897. Miller would leave PR&S Co. to manage recording for Edison’s National Phonograph Company in May 1897, while Hagen would briefly lead United States’ recording program before organizing Harms, Kaiser & Hagen in May 1898 with sheet music publisher T.B. Harms and New York Phonograph Co. recordist and exhibitor John Kaiser. Leeds would join with L. Reade Catlin to form the influential Leeds & Catlin in April 1899 while Walcutt would help Emile Berliner establish a gramophone company in France.

In November 1896, recording pioneer and sometime smut peddler Russell Hunting began publishing The Phonoscope just in time to document a major boom in the industry. The end of North American’s exclusive agreements allowed independent dealers (or, “jobbers”) to emerge, many of whom would maintain small recording operations while selling records and supplies manufactured by the majors. As with the North American sub-companies, many didn’t differentiate between these classes, making it difficult to know exactly who made what.

The other major development was the introduction of spring motors and cheap home phonographs. The first of these offered for sale were designed by Thomas MacDonald and manufactured by American Graphophone beginning in 1895. United States and Chicago Talking Machine debuted their motors in ’96 which could be sold alone or fitted to a graphophone or phonograph. National’s first spring-motor phonographs, like their first records, were manufactured by United States. Some discount models, like the Amet Echophone, the Euphonic Talking Machine, and the United States Talking Machine were also advertised in Phonoscope.

Some of the first independent record companies were organized by prominent performers from the earlier years – J.W. Myers recorded himself and others under his own name, then as the Globe Phonograph Company, then as the Standard Phonograph Record Company. Russell Hunting similarly recorded himself and others, first under his own name, then as manager of the Universal Phonograph Company founded by sheet music giant Jos. W. Stern. Edward B. Marks, manager of Stern and Universal, wrote in They All Sang that they considered recording a novel way to plug new songs and promote music sales. He describes their catalog of the standard New York talent but also states “any performer who came into our publishing house for professional copies was dragged down to the laboratory for a phonograph test”. Roger Harding recorded independently before selling his operation to the Excelsior Phonograph Company. George J. Gaskin and Dan W. Quinn advertised their status as free agents and recorded for most of the prominent companies.

Established stars George J. Gaskin and Dan W. Quinn, and up-and-comers Estella Mann and T. Herbert Reed

Most of the independent companies sought out the established talent, though some came to specialize in particular genres or instruments, or attempted to make stars of their exclusive performers. The Lyric Phonograph Company showcased records of Estella Mann when recording women was generally agreed to be prohibitively difficult. Reed, Dawson & Co. made a specialty of violin records and the Metropolitan Band. The Universal Phonograph Company marketed records performed by famous composer George Rosey and his band. The Kansas City Talking Machine Company took records of songwriter Hattie Nevada in addition to selling her sheet music. Many more independent companies developed small recording programs in Manhattan and advertised in Phonoscope. A map of Manhattan manufacturers and dealers assembled from Phonoscope reflects how congested the industry became.

As the recording companies preferred vetted talent at the front of the horn, they vied for the skilled service of qualified recordists behind it. Victor Emerson left the United States Phonograph Company to lead Columbia’s recording department, Walter Miller returned to working with Edison after several years of independence. I.W. Norcross left behind his own successful recording company also to join Edison’s ranks. Calvin Child settled into the Berliner Gramophone Company after making his mark on several cylinder operations.

Some companies specialized in supplies, such as horns, record cases and cabinets. The most prominent of these was Philadelphia based Hawthorne & Sheble who sold novel devices such as the clover-leaf horn before manufacturing disc records in the 1900s. F.M. Prescott offered glass horns in a variety of colors and finishes and a “cornet horn”, shaped like a bugle. The Greater New York Phonograph Company offered “chemically prepared linen fiber diaphragms”. The American Micrograph Company offered a horn with attached stylus that required no reproducer. Some others supplemented their business with magic lanterns, stereoscopes or motion picture devices.

As the decade drew to a close the market re-consolidated into the hands of those companies with the money, the talent, and the patents. Columbia consolidated with American Graphophone and leveraged their prominence as manufacturers and formidable patent pool against all competitors. Edison organized the National Phonograph Company in January 1896 and reduced or cut off the supply of blanks to the independent companies. In the same year, Emile Berliner would receive the investment capital and organize the manufacturing and sales structures that would allow the Gramophone to compete with, and eventually replace the phonograph.

Notes:

[1] Victor Emerson clearly dates the organization of USPC to spring 1893 in a relatively contemporary court testimony for the American Graphophone vs. USPC trial in 1896. Chicago’s organization is a bit murkier – a Feb. 1910 article in Talking Machine World notes the company was formed “18 years ago” to service the Columbia Exposition that took place in 1893. Even if the company was formed in name for that purpose, it’s likely they didn’t begin the recording and sales operation until after the fair was closed in October of that year.