Written by Mason Vander Lugt, National Recording Preservation Board

The First Book of Phonograph Records is a founding document of the recording industry, representing a log of recordings taken at Edison’s laboratory leading up to the first sales of musical records by the North American Phonograph Company in 1889 and 1890. It is now available in a digital edition here, presented by the National Recording Preservation Board, with scans courtesy of the Thomas Edison National Historical Park and National Park Service.

When the North American Phonograph Company was incorporated in July 1888, the Edison Phonograph Works were granted an exclusive right to manufacture phonographs and accessories, and North American the exclusive right to market them. North American wouldn’t deal directly with the public, but would license exclusive territorial rights to regional sub-companies, which were formed in the fall of 1888 and spring of 1889. These licensing agreements established that the Works’ exclusive right to manufacture phonograph supplies would include “special extras”, like recordings of music [1].

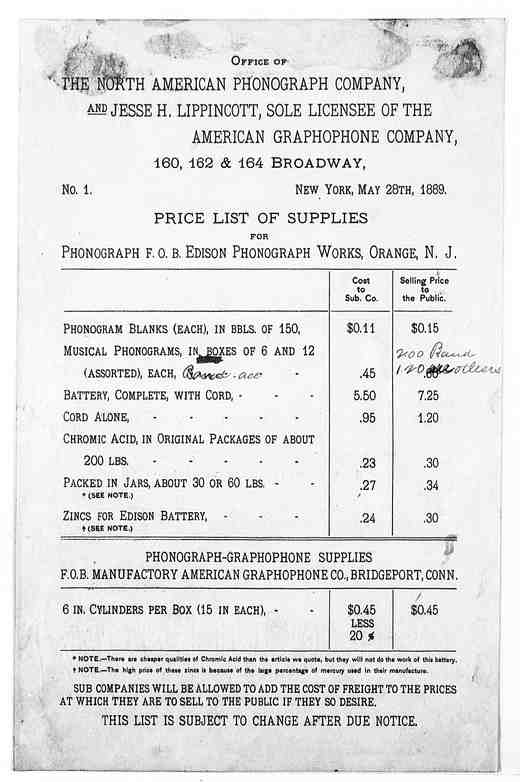

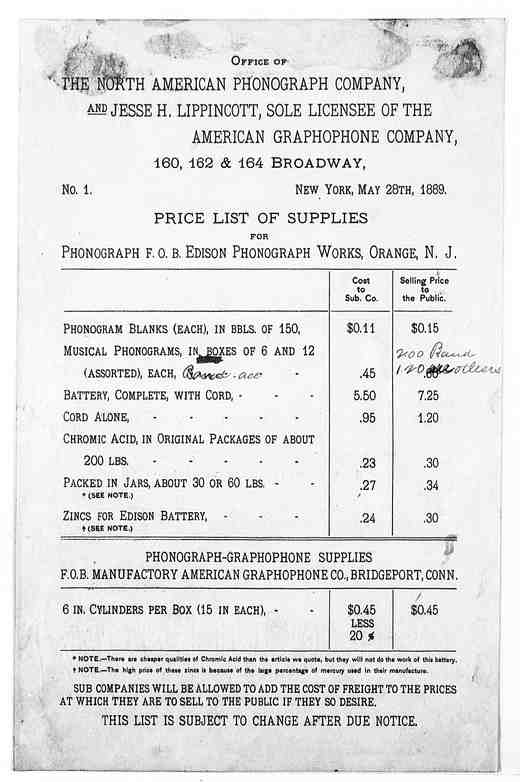

North American’s first list of recordings for sale, May 1889

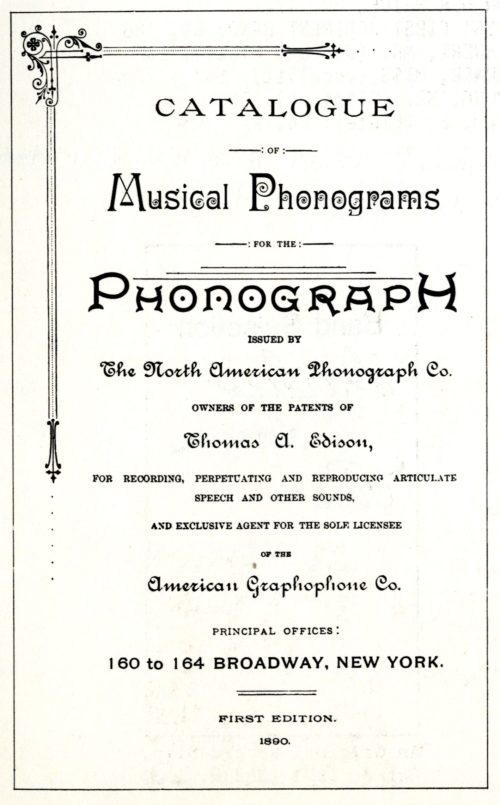

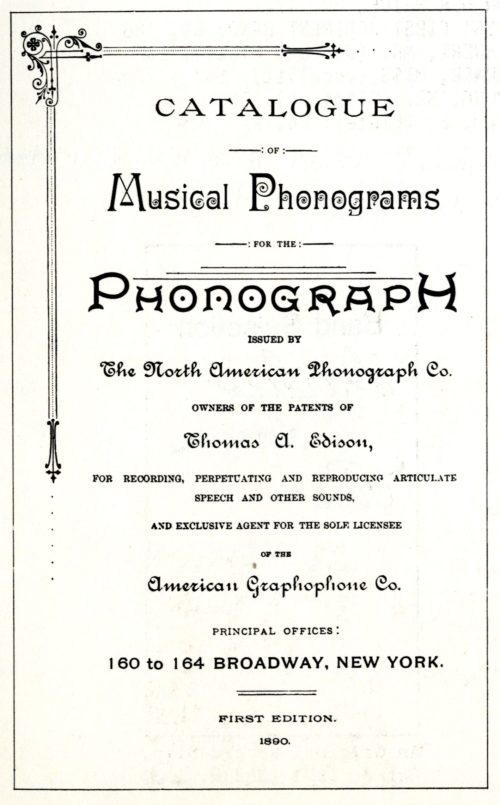

The first of these were sold in May 1889, in mixed lots of 6 and 12. A. Theo. E. Wangemann began logging recordings in the First Book only a few days before these were advertised, but had in fact been developing his process over the preceding year [2]. In December Thomas Lombard, North America’s vice president, urged the Works on the sub-companies’ behalf to publish a catalog of available recordings and allow them to choose what selections they would receive. The Works obliged and in mid-January of 1890, North American published the “Catalogue of Musical Phonograms for the Phonograph, First Edition” [3]. Little more than a week later, on Jan. 25th, Edison announced that he would be discontinuing the Works’ recording operation, apparently upset by complaints sent by the sub-companies [4], and suggested they should begin making their own recordings.

North American’s first catalog, January 1890

Roughly the first three quarters of the First Book represent the period between the first sales in May 1889 and Edison’s suspension of recording in January 1890. It provides insight into the state of the art, from cylinder shortages and machine malfunctions, to rates of success and productivity. It gives us a sense of the repertoire, some of which you’d expect, some which seem to be performers’ specialties. It documents the first sessions of future recording stars, like Edward Issler and George Schweinfest, and gives a rare glimpse at a generation of pioneer recording artists about which unfortunately little is known or likely to be found. The remaining quarter presents scattered clues about the Works’ come-and-go recording activities in the following years – a few more recording sessions, shipments for exhibitions, orders for repairs or duplication, and other various notes.

It’s worth noting that this is not the first time the First Book has been made available to the public. Allen Koenigsberg transcribed it for Edison Cylinder Records, 1889-1912, first published in 1969. As this important work becomes rare or expensive, we hope the First Book Digital Edition will ensure this portion remains available, as there is still important work to be done in researching this period in recording history. To this day, the recording activities of the North American Phonograph Company and its affiliates are poorly understood, partially due to the complicated relationships between the companies and partly due to patchy documentation. This resource and article represent the first in a series of studies on this topic. Readers are invited to send additions or corrections to mlug@loc.gov.

At the third annual convention of the sub-companies, Lombard noted that North American had made arrangements with the New York Phonograph Company to supply records shortly after Edison’s announcement [5]. North American began their own recording operation in February of 1890, or maybe January. Two letters dated February 24, 1890 offer clues – one to Edison from his secretary A.O. Tate saying “I think the North American people have started in on music business”, and another from the Vice President of North American Thomas Lombard to the sub-companies assuring they were “arranging to increase [their] facilities for making these records”. They published three lists of available recordings that year, one each in June, August and October, which are reprinted in Edison Cylinder Records.

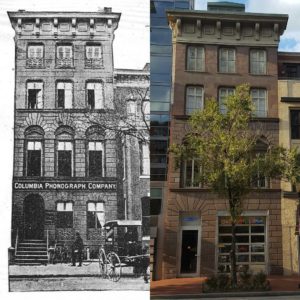

Several of the sub-companies took Edison’s offer to begin their own recording programs. In February 1890 the New York and Columbia Phonograph Companies published versions of the January 1890 North American catalog with additions or substitutions of their own. By the following summer the trade journal Phonogram noted “The securing of musical selections has grown to be quite an industry. It is done mainly by the Columbia Phonograph Company of Washington, D.C., the New Jersey Phonograph Company of Newark, N.J., the New York Phonograph Company and the Ohio Phonograph Company” [9]. The sub-companies role in developing the industry will be a future installment in this series of studies mentioned above, but in general, the sub-companies dominated the records market from fall 1890 until at least spring 1892.

In the meantime, Edison returned his attention to developing technologies to duplicate records, understanding that the limited scale of recording “by the round” was expensive and unnecessary. At the second annual convention of the sub-companies in June 1891, Edison invited the attendees to visit the Laboratory and Works, and proposed launching a service to duplicate their recordings. North American reluctantly agreed to permit the service in August after negotiating a royalty with Edison.

Judging from the discussion at the convention, the sub-companies were under the impression that the Works would either duplicate for a fee and return records to the sub-companies to market or that North American would sell the records and pay the sub-companies a royalty. In fact, the Works would surreptitiously acquire recordings taken by the Columbia and New England Companies and advertise them for sale [6]. The Works’ first and only catalog, published sometime in late 1891 [7], lists recordings taken at the Works between April and October (First Book pp. 180-190, 206, 208) alongside band, whistling, and recitation recordings recorded and marketed by Columbia. When Columbia and New England protested in December 1891, Samuel Insull (North American’s president) wrote to Tate that this approach was unsustainable, and requested he draft a response.

In his response, dated 1/12/92, Tate suggested they insist that the Works maintained the exclusive right to manufacture recordings, but would allow the sub-companies to continue making original (one of a kind) recordings if they would deal exclusively with the Works for duplication. The Chicago company had begun offering a duplication service at a lower rate [8]/[9], and Tate may have staged the event as a way of protecting the Works’ proposed service.

He told Insull that “The prices which now prevail are absurdly high, and the character of the records is very poor. It is only by employing an adequate method of duplication that the prices of these records can be brought down to a reasonable point, but this cannot be accomplished unless the work is concentrated in one spot, so that whoever takes it up can have the full benefit of that whole class of manufacture”.

Tate must have had an interesting evening, because the day after writing the above, he wrote to Edison proposing nearly the opposite – that the Works discontinue their recording program and duplication service (to the local companies) and enter into an agreement with independent recordist and entrepreneur Charles L. Marshall [10] to supply a large number of duplicate recordings for the New England, New York, and New Jersey coin-slot markets. Insull wrote to Edison to give his support to the idea in late January, and a draft of the proposal was written in which the Works would manufacture recordings and duplicate Marshall’s, sell them to Marshall with North American’s consent, and Marshall would distribute them across the northeast with Edison’s legal protection.

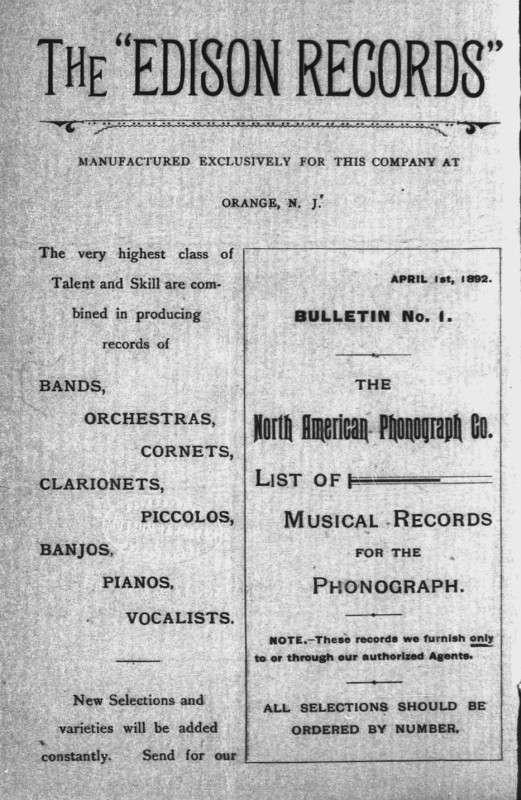

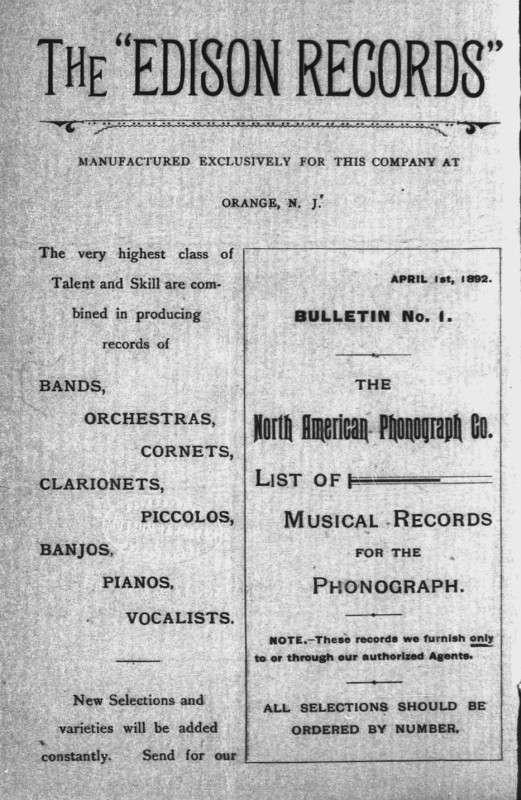

The agreement seems to have fallen through, but the concept of re-centralizing the business had stuck. Shortly after, the Works and North American would again join forces to manufacture and sell recordings, anticipating a larger consolidation of the company later that year [11]. The Works resumed recording in February, and in April, North American published “Bulletin No. 1 – The North American Phonograph Co. List of Musical Records for the Phonograph”. Advertisements in Phonogram were headed “The ‘Edison Records’ / Manufactured exclusively for this company at Orange, N.J.”.

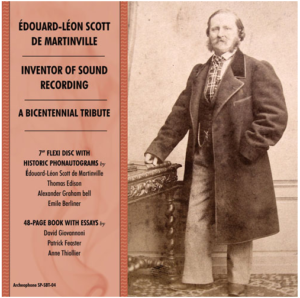

The first catalog of North American’s “Numbered Series”, which ran April 1892 – August 1894. Image from Phonogram Vol. 2 No. 10

The first of these must have been from the recording sessions listed in the First Book, pages 192-211. After this, it’s likely that master records were taken at the North American headquarters in New York, but that duplication continued at the Works. At the annual convention in June 1892, Lombard told the sub-companies that their goal was to compete with them directly with the advantage of low-cost, high quality duplicates [12].

North American advertised heavily in 1893, including a brochure advertising phonographs for home entertainment. By March 1893, recordings were taken at a dedicated facility at 120 E. 14th Street, New York [13]. At least one surviving example – Silas Leachman’s “Daddy Wouldn’t Buy Me a Bow Wow” was recorded at the company’s offices in Chicago.

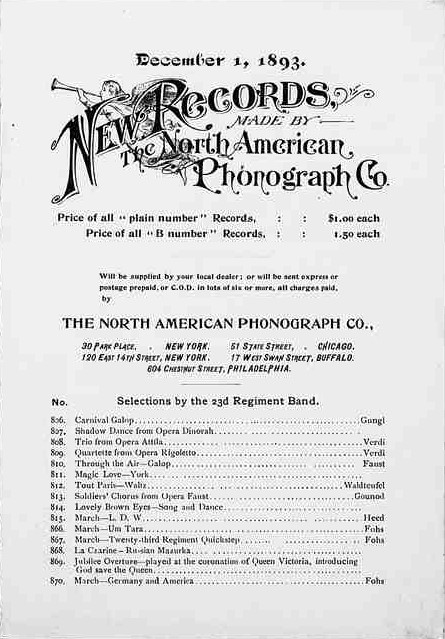

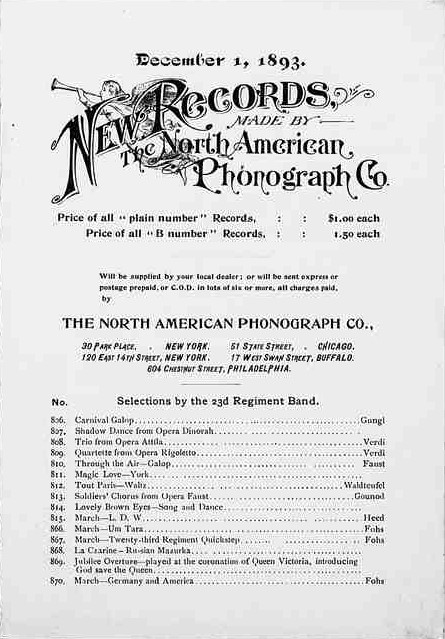

North American’s December 1893. The last known to the author.

A September 1893 letter from Tate to Edison gives us a rare overview of the business – the joint North American / Works recording operation had made 18,600 records and had shipped 7,100 [14]. They had 120 selections to choose from. He said that there had always been more of a demand for recordings than available supply, and estimated that the market could support 150 to 200 thousand records per year. By November the catalog showed that the number of selections had cumulatively reached more than 800. By December, 880.

Tate’s gamble seemed to have worked. North American’s recording program grew steadily, while at the fourth and final convention in September 1893, R.T. Haines, president of the New York Company complained that demand for high class records always outpaced supply and that high-quality duplication was unavailable to the sub-companies [15]. Columbia, as usual, was the major exception, having purchased Leon Douglass’ patent in June 1892.

North American’s accounting ledgers show continued recording and sales until the company’s collapse in August for reasons having little to do with the recording business [16]. Coming full-circle, the company supplemented their supply of original recordings by purchasing from the New York Phonograph Company. The August 20 “closing entries” in the ledger estimate $5,200 worth of musical records unsold.

Notes:

Like this:

Like Loading...