(This is a revised and expanded version of the article that appeared in IAJRC Journal, Vol. 48, No. 4, December 2015)

Records appear in films from the silent era fairly often. One would think an image of records being played onscreen would be something to avoid in the era in which movies were accompanied by live musicians. On the contrary, records used, played and heard by actors in a motion picture could be everything from casual to a definite, and significant, placement in a picture.

Buster Keaton takes a record off his Grafonola turntable and hangs it on the wall in The Scarecrow, a 1921 comedy short.

It appears to be a “Magic Note” Columbia label, though we never get close enough to see for sure.

In this case it’s irrelevant, as the point is that Keaton has turned his machine into a stovetop and an oven.

«»

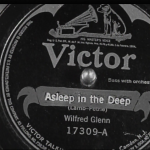

In The Navigator, Buster Keaton’s memorable 1924 comedy feature in which he and a girl are marooned on a cast-adrift ocean liner, the record Asleep in the Deep, sung by Wilfred Glenn and  recorded in 1913 on Victor 17309, makes a strong showing. It looks like the song title on the record label was highlighted to direct our attention to it. Due to the rocking ship, the Victrola’s turntable is accidentally started. Though we know Keaton and the girl (played by Kathryn McGuire) can hear the record, we’re aided by the song’s lyrics being superimposed on the shot of the Victrola.

recorded in 1913 on Victor 17309, makes a strong showing. It looks like the song title on the record label was highlighted to direct our attention to it. Due to the rocking ship, the Victrola’s turntable is accidentally started. Though we know Keaton and the girl (played by Kathryn McGuire) can hear the record, we’re aided by the song’s lyrics being superimposed on the shot of the Victrola.

As this recording had already been around for ten years and the song was also recorded for all the other labels, not to mention being a common salon concert selection, presumably lots of people in the audience were familiar with it.

«»

In 2004 I was hired by the Milestone Film and Video company to record scores for several comedy shorts to be included on their forthcoming Charley Chase DVD set.

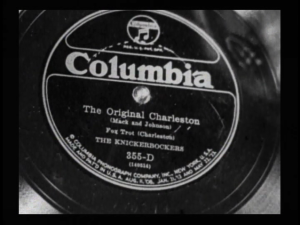

The opening shot of Mama Behave, a 1926 Hal Roach comedy directed by Leo McCarey, is the label: The Original Charleston by The Knickerbockers, recorded in early 1925 on Columbia 355-D. Naturally, I imagined having the chance to play The Charleston by my idol and favorite hot pianist: James P. Johnson.

However, I was instructed not to play The Charleston as the cost of clearance would be more than the cost of producing the whole DVD set. “Just play something Charleston-esque,” I was told. My heart sank as I worried that anybody watching would think: “Why isn’t the piano guy on this DVD playing The Charleston?”

The record label sets the stage for this wild comedy in which Charley doesn’t want his wife to think he can do The Charleston, though in fact he’s an excellent dancer.

⇒⇒⇒

«»

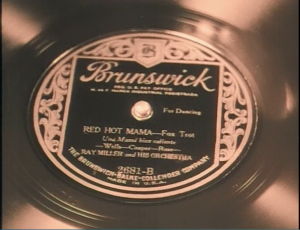

In Mary Pickford’s last silent film: My Best Girl, directed by Sam Taylor and released in 1927, the record Red Hot Mama by Ray Miller and his Orchestra, recorded in New York on August 5, 1924 and released on Brunswick 2681-B, plays an important part near the end of the movie. Pickford plays a shopgirl who’s afraid she’ll be rejected by her boyfriend’s (Buddy Rogers) father (the wealthy owner of the department store where she works) for being poor. She makes a last-ditch and ridiculous effort to convince Rogers that she’s a bad girl by playing Red Hot Mama on the Victrola and doing a naughty flapper dance, much to the bewilderment of her puzzled parents.

In Mary Pickford’s last silent film: My Best Girl, directed by Sam Taylor and released in 1927, the record Red Hot Mama by Ray Miller and his Orchestra, recorded in New York on August 5, 1924 and released on Brunswick 2681-B, plays an important part near the end of the movie. Pickford plays a shopgirl who’s afraid she’ll be rejected by her boyfriend’s (Buddy Rogers) father (the wealthy owner of the department store where she works) for being poor. She makes a last-ditch and ridiculous effort to convince Rogers that she’s a bad girl by playing Red Hot Mama on the Victrola and doing a naughty flapper dance, much to the bewilderment of her puzzled parents.

Ray Miller’s records are not too hard to locate to this very day. Perhaps his band’s popularity set the stage for public acceptance of another future bandleader named Miller.

«»

Not all of the appearances of records in the silents are in comedies. One of the most remarkable films of the late silent era is The Crowd, directed by King Vidor for MGM in 1928. Near the final curtain of this film there is an emotional reconciliation between the characters played by James Murray and Eleanor Boardman with help from There’s Everything Nice About You, by Johnny Marvin accompanied by Andy Sannella on Victor 20612 and recorded in 1927, played on their portable wind-up machine.

(I wasn’t able to snip this image because this film has never had a DVD release and it’s not on You Tube.)

«»

When Jimmy Finlayson sets a stack of records on top of a Victrola in front of his store in Liberty, a 1929 MGM Hal Roach comedy directed by Leo McCarey and starring Laurel and Hardy…

…we know what’s coming.

Smashing records is funny, I suppose, though the first time I saw this I said “Oh no!” If only we could have had a chance to see, one disc at a time, those nice new records.