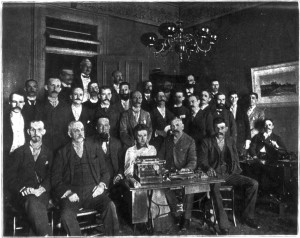

In May 1890, the representatives of the regional subsidiaries of the North American Phonograph Company met in Chicago to discuss the future of the phonograph business. In the preceding two years, the phonograph had developed from a curious toy into a useful tool, and the major patents had been consolidated into an enterprise that was positioned to make a fortune if conditions were favorable. Modeling after the telephone company, North American licensed rights to 28 regional sub-companies to exploit the technology in their respective territories. They were tasked with building an industry, and the opportunity must have seemed limitless.

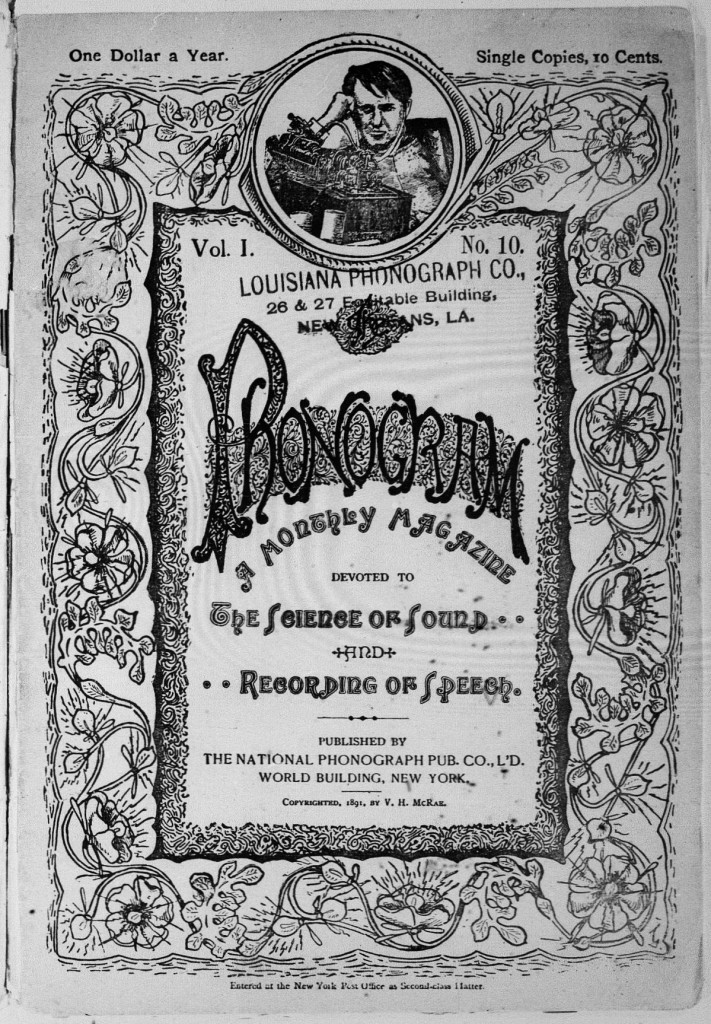

Virginia H. McRae was a typewriter entrepreneur from Wilmington, North Carolina. By 1885, at 35 years old, she was running her own successful copying business in New York. The newspapers back home called her “plucky”, “energetic”, and “properly very proud of her independence”. When it was decided at the 1890 convention that a trade journal might benefit the association, Thomas Lombard, Vice-president of the New-York based North American Company was charged with investigating the prospect, and may have already had an editor in mind.

In The Phonogram’s first issue, published January 1891, McRae stated her purpose plainly:

The object and scope of the Phonogram […] is to familiarize the public with the good qualities of its namesake, to preserve the record of its growth while it moves forward to the achievement of the highest possible good, and to illustrate the part it performs in the work of human progress.

To understand the vision and influence of The Phonogram, it’s worth reviewing the basics. In January 1891, buying a phonograph to use at home wasn’t even an option. The spring-power mechanism that allowed the machines to be safe and efficient was still years in the future. The phonographs of 1891 were mostly powered by unwieldy and unreliable batteries, or treadle. Some were hand-cranked, some tapped into light sockets. One ill-fated model even used water-pressure.

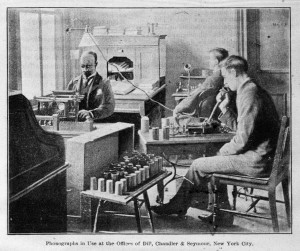

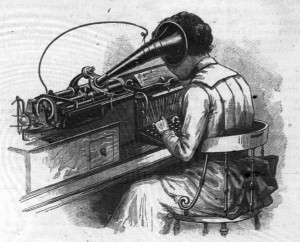

Use of the machines could be generally categorized as business or entertainment. In a business setting, the machine mediated the process of dictating speech. Where before a speaker had to maintain a pace the stenographer could keep up with, or accept inaccuracies or losses, a phonographic secretary or reporter could quietly repeat what they heard into the recording tube while an assistant maintained continuity between two machines. The recordings would likely still be transcribed to type, but it made the process more natural and more reliable for speaker and stenographer alike.

“These early adopters have got electric light, a telephone, a phonograph and a typewriter” (vol. 3, no. 1)

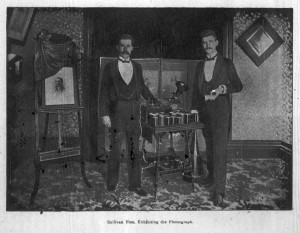

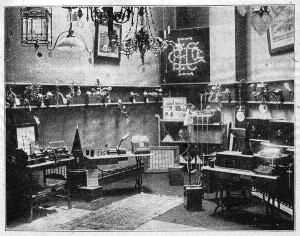

In an entertainment setting, the most common model was the public exhibition, made possible by the invention of the automatic, or ‘nickel-in-the-slot’ machine. At first, machines were placed one at a time in drugstores, saloons, hotel lobbies and train stations. Patrons would place stethoscopic ‘listening tubes’ in their ears, put a coin in the slot, and the phonograph would play the recording of the day – instrumental solos or ensembles, popular songs, bands, as well as humorous and dramatic recitations, or reenactments of historic speeches . As this practice gained popularity, exhibitors rented booths or rooms at fairs, and eventually entrepreneurs would devote entire parlors to phonograph (and eventually kinetophone) entertainment.

Another business model for entertainment was the phonograph concert. Like the medicine show before it, a traveling phonograph exhibitor would advertise events, usually in more suburban and rural areas where patrons wouldn’t encounter automatic machines in public. They would sell tickets to the event, held in a town hall, clubhouse, church or fairground, and the audience would hear recordings brought from all over the country. Sometimes recordings would be made on the spot and reproduced for the audience.

The Phonogram was only in publication from January 1891 to April 1893, but in this short time it reflects the symbiotic growth and (growing pains) of the industry and culture of sound recording from the ground-level view of the practitioners. In a time when North American’s administration saw a cheap stenographer, The Phonogram and the local companies behind it explored every possibility, including:

- Home phonographs and records

- Music by phone

- Records by delivery

- Audio news by delivery

- Voice-letters by mail

- Educational lessons, especially of language

- Ethnographic field recording

- Preserving family’s voices

- Recording telephone conversations, and answering-machine functions

- Audio books

- Speaking toys

- Speaking clocks, including alarm clocks

- Sermons

- Weddings and funerals

- Comforting the dying

- Scientific recording, including field recording

- Transposing sounds outside the human audible range (insects)

- Recording secretly for legal evidence

In addition to brainstorming phonograph applications, the magazine documented developments in the typewriter, telephone, electrics, and in later issues, motion picture (2:10). It provided a venue for opinion articles, like “Give Every Family the Chance to Use the Phonograph” (1:5) “The Phonograph Aids in the Progress of Women” (2:6), or “Typewriter Mechanics: Shift-key or No Shift-key – Which?” (1:4).

It announced news that would impact the local companies, such as North American president Jesse Lippincott’s assignment (1:4), and Edison’s appointment as president (2:7). Events of interest to its readers, like Electric Light Conventions in Montreal (1:8) and Buffalo (2:2), or celebrity recording sessions, as of Pope Leo XII (3:3-4), Sarah Bernhardt (2:11), and the Queen of Italy (3:2) also found a place.

It reprinted the programs of phonograph concerts (1:5, 2:4-5, 3:1, 3:2) and lists of recordings by the various local companies, which are otherwise virtually unknown today. It featured the successes of local companies, including Columbia (1:4), Louisiana (1:6-7), Ohio (1:11-12) and Chicago (2:4-5). Essentially, it filled in the gaps between annual conventions, and let the public in on the fun. Considering only 2-3% of recordings from this era survive¹, contemporary literature such as Phonogram and the transcripts of the annual conventions may be the best source for understanding the culture and industry of recorded sound in these formative years.

Phonogram is also rich with photos and illustrations. Some of my favorites are below, but I encourage you to take a few minutes to browse the issues on Archive.org for more.

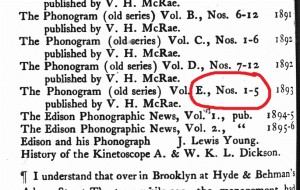

So what happened? When the last issue I could find (Vol. 3, no. 3-4) was published in the spring of 1893, people may have been a bit preoccupied by the World’s Fair in Chicago, but North American was in an upswing, and the magazine had never looked better. There’s no mention in the issue of plans to cease publication, it’s not discussed at the 4th convention in Sept. ’93, and I couldn’t find any mention in the Edison Papers Digital Edition. I don’t have an answer, unfortunately, but I may have found a clue. I scanned Phonogram from two microfilm sources. One of the reels was shared with another publication titled Phonogram (Phonogram II, or ‘New Phonogram’), published by Edison from 1900-1902 (also online). In issue 9 of Phonogram II there’s a list of ‘Edisonia’ in the library of the editor that includes a volume 3, number 5 of the original series. Maybe, if it exists, it’s explained there.

The North American Phonograph company, from 1888-1894 to me represents the ‘wild-west’ of the media frontier, and The Phonogram a contemporary, first-hand account of its players and events. In the following years, technical developments and industry consolidation allowed the phonograph to become a viable consumer good. The wax cylinder remained the dominant format, while the stage was set for the seemingly inevitable takeover by the disc format. To read more about this next chapter, browse Phonoscope, uploaded by the Library of Congress and Media History Digital Library in 2014.

The National Recording Preservation Board has begun scanning historical audio serials for inclusion into the Media History Digital Library and Archive.org for public access. An index will be available soon at the Media History Digital Library web site, but for now you can view the issues on Archive.org. Thank you to media historian Patrick Feaster for lending the microfilm reels that made this project possible.

¹https://www.loc.gov/programs/static/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/klinger.pdf

I have paper copies of the Phonogram from may, 1900. Is it valuable?

Hi Timon, this is Mason. In a 2014 auction I found online (link), the sale price ranged from $1 to $20 per issue! So your guess is as good as mine! I have a question for you, actually. The May 1900 issue I scanned was missing its cover. Is the cover in the same style as the second issue? (online here)

4 years late, but I don’t suppose you ever found that 5th volume of Phonogram 1893?