Editors note: This was originally presented by Dr. Lidia Camacho at the 2006 IASA Conference in Mexico City. It was printed in the July 2007 IASA Journal (no. 29) and is reprinted here with permission. Ten years later, the Fonoteca Nacional has achieved many of these goals and remains at the cutting edge of audio scholarship and public education through an active calendar of concerts and lectures, daily and weekly podcasts, galleries and exhibitions, recording and preservation studios, online collections, regional listening centers and more. Visit their site at fonotecanacional.gob.mx

Born out of substance and raised by senses and desire, memory is the most complete and perfect of human symbolic constructs. Though generated by individuals, its essence merges with the social being and, through an efficient path of communication it manages to become part of that common heritage that lives on through generations: tradition. Without memory there is no tradition, culture, roots, or product we can call our own, since memory is for each of the five senses, and for each human being the ground on which they sit and the beginning of their reason for living.

Memory, in individual and social terms, gets deposited in innumerable external niches, and gets shaped almost without sensing the different patrimonies which, over the years, become the extremely rich heritages of peoples, nations and the world. Unfortunately, the full value of those heritage is not appreciated, and this has led to the ruin, disappearance, and oblivion of more than a few of the riches we possessed until fairly recently.

That lack of attention and care of cultural heritage has reached very high levels in Latin America, especially with regard to sound and audiovisual archives. In that respect, it should be said that in Mexico there is an urgent need for a site dedicated to preserving our national heritage of sound. It runs a very serious risk of disappearing, not just because of the fragility of the analogue media on which it is held, the technological obsolescence of the instruments capable of reproducing it, and the imminent disappearance of this analogue equipment, but above all because this country lacks the tradition of conserving this intangible patrimony.

This lack of awareness has hindered appreciation of the enormous wealth contained in a sound archive and its virtually unlimited possibilities for the most diverse uses. These range from social, political and entertainment uses, to educational and cultural ones, where its value rises, since the sounds that characterise our daily life shape our identity, differentiating us from other cultures. Clearly, if we lose this heritage, part of our deepest being will disappear forever.

In Mexico, there are public educational and cultural institutions that have begun the task of archiving sound collections resulting from radiophonic production, research and the rescue of sound and musical manifestations. This labour has been carried on more with imagination than with sufficient economic and technological resources. This is why we believe it is particularly important for the public sector to implement a decisive policy to systematise the conservation, dissemination, and physical and intellectual control of sound resources.

It is therefore vital to have the guidance of adequate State policies that base its actions on the awareness of the fragility of the sound materials, and of the impending technological obsolescence of traditional sound media and equipment. Such a State policy would encourage the creation of appropriate strategies for conserving the sound heritage of Mexico to ensure access to that part of our identity by all the Mexicans. Moreover, it should foment awareness in the educational sphere of the value of sound documents, and promote the preservation of sound archives. Mexico’s audiovisual stocks are indeed still young: the oldest – UNAM’s Film Library – was created in 1964. For their part, video libraries like those of the Directorate General of Educational Television. Channel 11, Channel 22. TV UNAM, and the National Video Library itself, are still younger authorities that have grown rapidly for reasons particular to the mission of the institution to which they belong. Strictly speaking, however, they still do not have a long-term guarantee for their conditions of preservation.

This situation places us at a clear disadvantage compared with other audio libraries around the world. However, this has begun to change as a result of fact that the Secretariat of Public Education and the National Culture Council, through Radio Educación, have formed a culture of preservation of the country’s sound patrimony and taken the first steps towards implementing that State policy I mentioned earlier.

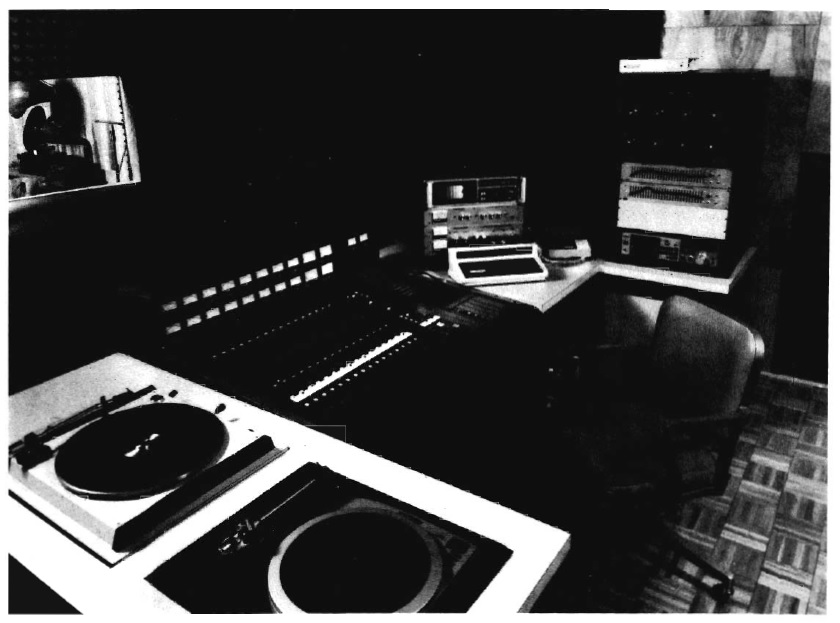

Accordingly, almost six years ago, Radio Educación embarked on a battle in Mexico against the laxity and ignorance that was allowing one of our most valuable legacies to disappear. I believe that we have managed to plant a seed of awareness of the importance of the country’s sound and audiovisual patrimony in Mexico. The battle has been fought on various fronts: on one hand, from our studios and broadcasting cabins, with radio programmes broadcasting samples of the world’s principal resources, or promoting the culture of preservation of humanity’s patrimony of sound; on the other, with the creation of the Mexican Standard of Phonographic Documents, an indispensable tool for the work of cataloguing sound materials from Mexican institutions. Finally, with the organisation of various national and international forums, such as seminars on sound and audiovisual archives.

These actions are joined today by another, which is about to become a tangible reality: the National Sound Library, an institution that will guide the particular policies of the educational and cultural sector aimed at safeguarding the country’s sound legacy, and which is an essential part of the National Culture Plan 2001-2006 implemented by the Mexican State to govern its actions in the vast and complex field of national culture. This newly formed institution already has a building to house it: the Casa de Alvarado (so called because it was where Pedro de Alvarado, the famous captain of Hernán Cortés, lived). With a space of over seven thousand square metres, the National Sound Library will be a centre truly dedicated to sound.

The mission of the National Sound Library will be to acquire, preserve and disseminate the nation’s sound heritage, so that present and future generations will have access to Mexico’s legacy of sound, through the processes of documentation, preservation and conservation. Consequently, the resources of the National Sound Library will comprise voice, music, radio and soundscape collections, as well as the legal depositing of sound recordings published in Mexico. This institution will therefore support a great many activities beyond that of preservation of the patrimony of sound. These will turn it into a living institution, a ceaseless promoter of the culture of sound, through a wide range of activities controlled by a well-planned strategy. The National Sound Library of Mexico will organise various cultural activities in and outside its facilities. One of these will be the exhibition of artistic manifestations related to sound. This area will include the presentation of sound sculptures. as well as performances and installations using sound as the raw material of their work. The National Sound library will also organise seasons of music, and sound art concerts, for didactic purposes as much as for pure recreation. No less important will be the auditions of various artistic expressions based on sound.

Similarly, the National Sound Library of Mexico will organise rounds of conferences with educational and recreational objectives, with the aim of strengthening the culture of preservation of the sound in a pleasurable and sustained manner.

Together with these activities, research into sound and its different manifestations, and fields of study, will occupy a privileged position in the new institution. That will broaden this area of knowledge so little explored in Mexico until now.

Such research will have two main guides: science and art. The scientific research will explore not only acoustics but also the history of mentalities, socio-biology, and other related fields. Investigation in this field will be done, using firm, clear foundations, into the value of the nation’s sound heritage, and into the scope of sound ecology. At the same time, strategies will be established to enable Mexico’s soundscape to be recognised, recovered and disseminated. With regard to the aesthetic directive, the research will be aimed at inquiring into the history, prospects and scope of sound art, an aesthetic expression that has opened up the possibility of treating sound (per se, and not just musical sound) artistically, and that now has more than a century of history, with representative works now forming part of the history of universal art.

Additionally, the National Sound Library of Mexico will have an extensive and concrete programme of printed and electronic publications to enable it to disseminate both the ideas generated within our institution and those coming from outside, so as to breathe new life into our works.

Training, without doubt, occupies a special place because we feel the formation of human resources is one of the tasks vital to preserving sound archives. A national and international programme of courses, workshops, diplomas and seminars on the different fields of conservation, documentation, and preservation of sound will therefore be designed, with the consequent benefit to the people who are interested. This will help us achieve the very necessary formation of professionals in the area of documentation, conservation, restoration and digitisation. IASA will have a leading role in this programme, since its support will be essential to bringing our academic objectives to fruition. However, the National Sound Library will also have other fields enabling it to influence the national stage in Mexico. One of the most important is that of promoting artistic sound experimentation, no longer from the perspective of research, but from that of creation, to produce works of sound art with the involvement of the most distinguished representatives of this manifestation and, in turn, to disseminate much of what has been made in this field of contemporary art. In this sense, the tasks of the Artistic Sound Experimentation Laboratory (LEAS – Spanish acronym), conceived as a space for researching and investigating the possibilities of sound art, will take on particular importance. Moreover, the National Sound Library of Mexico will base part of its actions on the educational and cultural possibilities of sound collections. To do this, it will create a sound stimulation programme with educational and artistic aims directed at children. Furthermore, the educational use of the National Sound Library’s sound documents will be promoted in the classroom, with a view to encouraging an appreciation for records of musical and oral memory, and micro-history, among children and young people. In the same way, teachers will be involved in the handling of the sound, acoustic and musical medium in the classroom. Public presentations of sound collections from the National Sound Library will also be promoted.

Additionally, in order to promote the knowledge and use of its resources, the National Sound Library will have a range of access and dissemination services. These will be in various formats, making our institution an informal space for meeting, research and education based on sound.

Among the most important of these are the audio library, both on site and online; the supply of online programming designed according to demand from the various educational centres; sound experimentation workshops, and electro-acoustic and acoustic music workshops, applied to creative and communicational processes; courses on musical appreciation and radiophonic appreciation; and the exchange of resources.

No less important will be the guided tours, where visitors can have a new experience given the great wealth of sound, and where they can enjoy a marvellous sound garden of over 600 square metres.

It has taken six years of intense work on behalf of Mexico’s sound heritage. Every idea, every action, every step has been guided by passion and patience, by imagination and intelligence, but above all by a profound conviction that the conservation of sound memory is our prime commitment to future generations – those who, with other ears, will have to ask us what we did with what has always belonged to them, and what our time sounded like as well as that of bygone ages. Today, more than ever, I feel enormous satisfaction to be part of the birth of a new institution that will strengthen our national identity and at the same time enrich the world’s cultural resources.

The Fonoteca hosts sound-walks and sound-tracks (by bicycle) to encourage visitors to listen closely to their surroundings. Photo from Caminata Sonora Por el Zócalo de la Ciudad de México. Not included in original article.