The Librarian as Activist: Harold Spivacke and Recorded Sound – Donald L. Leavitt

Reprinted from Recorded Sound no. 79, (Oct. 1979) by permission of the British Library Sound Archive. The photo was not included in the original article but was added here to illustrate.

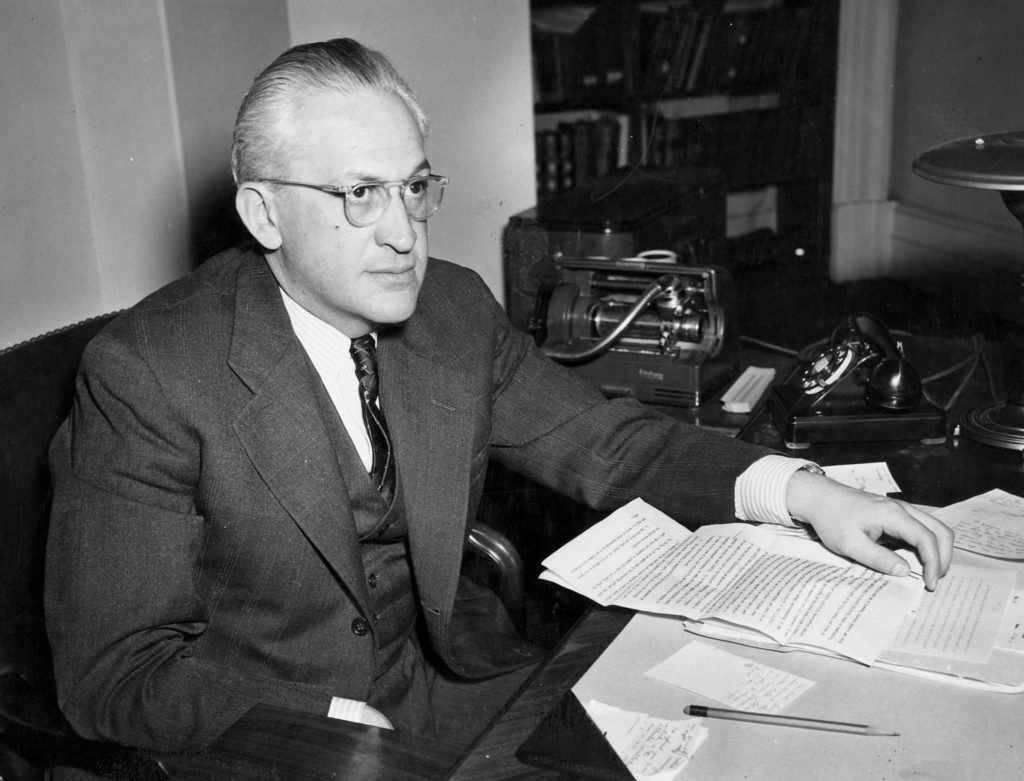

Harold Spivacke, 1946 – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (detail – see original)

Of the seven men who have served as Chief of America’s greatest music library, Harold Spivacke enjoyed (a particularly apt usage) the longest term by far and saw its most diversified growth. The last verb is as misleading as the previous one is felicitous. Although an avowed believer in ‘historical accident’ himself, Spivacke perceived opportunities in events and, through those, caused much of the present shape of the musical collections, services, and activities in the Library of Congress, and to a degree, of events in the musical world in general. Manuscripts from Broadway and Tin Pan Alley looked odd on library shelves when he first placed them there. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge’s gem of a chamber music hall at first seemed an unlikely recording and broadcasting studio, and a less likely oral history workshop for Alan Lomax and Jelly Roll Morton. To begin to list the composers and musicians whose careers have been significantly affected by Spivacke – even alphabetically – would be undiplomatic. To complete such a list would be impossible.

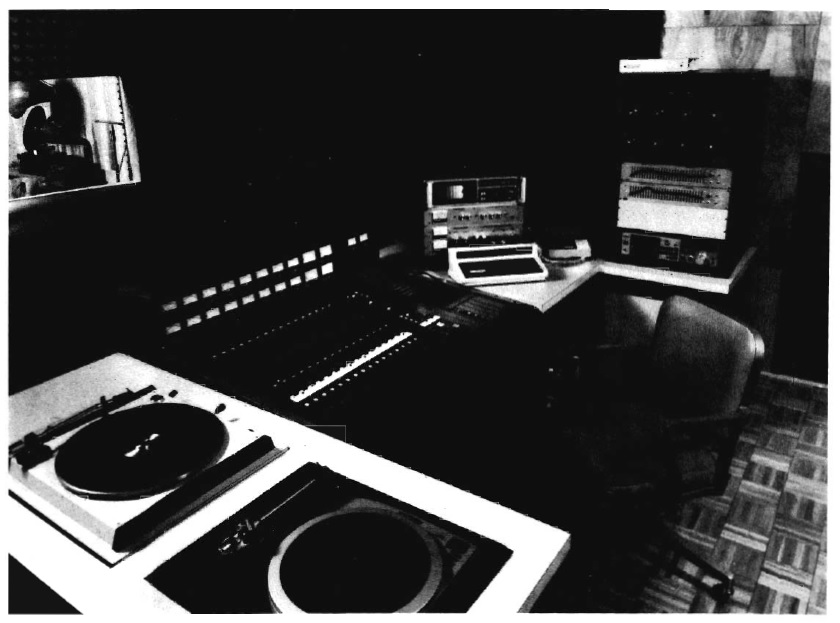

Anyone who has read a life of Edison knows that his ‘favorite invention’ was the phonograph. Spivacke, another man who had a life-long love affair with the physical sciences, mechanics, and ‘gadgets’ was proudest of the Library’s Recording Laboratory among the many ‘historical accidents’ which he precipitated.

The medium of recorded sound made its first appearance in the Library of Congress – barring its undoubted use as a stenographic tool – around 1906, when E.W. Scripture presented the Librarian, Herbert Putnam, with a cylinder of the voice of Wilhelm II. Evidently it did not make an impact as an important kind of documentation until after it was retrieved from Mr. Putnam’s safe more than thirty years later.

The gifts of Victor Red Seal discs, first made in 1924, and periodically supplemented, appear to have been unsolicited. The Library’s role appears to have been that of passive recipient. The active recruitment of the rest of the industry to follow suit was initiated by Spivacke about fifteen years later and continued by his staff until the Congress recognized the medium as copyrightable in 1972. Even Victor, the initial donor, had limited its generosity to the elite Red Seal product until Spivacke persuaded them of the breadth of the nation’s archival needs. Throughout those three decades of increasingly active gift solicitation Spivacke was fully aware that the exercise was a temporary stop-gap as he looked forward to a legislative solution. Writing in Library Journal in 1963 he referred to the hoped-for new law and anticipated ‘… a legal requirement to deposit records manufactured in the United States [as] the only way that we can be assured of preserving our productions for future generations.’ He followed the law’s long and arduous course with keen interest, and had the pleasure of seeing the recording deposit provisions implemented in January, 1972, a few months before his retirement from the Library. He was no less interested in the other aspects of the new law, particularly its ‘fair use’ provisions, which he was studying and discussing with characteristic perception and conviction quite literally to his last days.

But to return to that ‘favorite invention’, the Recording Laboratory, we all know that the first scholarly applications of the talking machine were made by scientists involved with audible ethnology, anthropology and linguistics. It is merely historic, if not poetic justice that the operation which first germinated the need for a recording laboratory in Harold Spivacke’s mind was that of his ethnomusicologal unit, the Archive of Folk Song. As has been noted, he had a scientific turn of mind, had recently written his doctoral dissertation in acoustics, was familiar with Hornbostel’s work in Berlin and was at home in sound laboratories. While such laboratories were new to libraries when the Carnegie Corporation established one in the Music Division in late 1940, they were not new to Harold Spivacke. Needless to say, other uses undoubtedly occurred to Spivacke before he could say ethnomusicology which he would not have said, since the word hadn’t yet been coined. He had already recorded the April 1940 Coolidge Festival of Chamber Music with borrowed equipment, and immediately commenced the regular recording of the concert series for the collections – like the Archive, providing another example of the librarian’s role as generator of his own acquisitions.

It was Carnegie’s intention that the Recording Laboratory be self-supporting, principally through the sale of copies of the field recordings in the Archive of Folk Song. From the sale of individual copies it did not take long for the Library to enter the record manufacturing business. At that juncture, historic justice wasn’t the only consideration. The Archive was there, of course, but this fact meshed neatly with the fact that folk music seemed safely enough in the public domain and free of copyright problems. For an administrator remembered as an innovator, his record publishing policy seems conservative today. Songs with possible copyrighted progenitors were eschewed, as were artists with viable commercial appeal (many did eventually turn up on commercial labels after having been discovered by the Library’s collectors). Just as Spivacke was always sensitive to the rights of copyright claimants he deferred to the record industry on whose generosity the increasing flow of gifts depended. Some record industry officials who later benefitted from the folk music ‘boom’ thanked him for having contributed to it. In keeping with the strictly non-commercial image of the folk music series, Spivacke early enunciated to his staff the policy that nothing would ever be deleted from the catalog. As far as content is concerned nothing has been (discounting the format change to LP and some ‘take’ substitutions) since the first ‘Friends of Music’ album appeared in 1941!

Archival material with commercial possibilities or involving artists with record industry contracts was enthusiastically made available to the industry itself for marketplace channels of distribution – once all the necessary copyright clearances and artists’ permissions were supplied. Thus appeared the famous Lomax-Morton interviews and a substantial body of Woody Guthrie performances on commercial labels, as did legendary performances by Bartók, Szigeti, Arrau, Busch, Serkin, and the Budapest String Quartet, all recorded by the Library’s Recording Laboratory.

While the Laboratory has served the Library as a generator of material for the collections, and has served the public by disseminating it, its scientific research capabilities figured importantly in Spivacke’s long-term thinking. It was through his efforts that the Rockefeller Foundation funded the first concentrated research into the archival storage of recorded sound, and in the Laboratory that the research was coordinated. The Laboratory continues to be a testing ground for equipment and techniques for the benefit of its own collections and services and those of other libraries and sound archives. Spivacke stayed remarkably abreast of the newest technical developments to the end of his life, just as he followed the progress of the copyrights law. He was always among the first on the staff to try a new video recorder, or ultrasonic cleaning bath with the same experimental enthusiasm which years before had taken him with John Lomax to record Jimmy Strothers’ spirituals at the Virginia State Penitentiary.

We have spoken of Spivacke’s having represented the librarian as generator of his own acquisitions. Years before Spivacke when Carl Engel was Chief of the Music Division, Mrs. Elizabeth Coolidge had placed the Library of Congress in the unusual position not of recording, copying or publishing a work, but of playing a role in its creation. Not altogether unusual, perhaps, if one reflects upon some illustrious examples of librarians as authors and (remember Berlioz!) even as composers. Nevertheless a foundation for the commissioning of new chamber works was a novelty in libraries when Mrs. Coolidge offered one to the Librarian of Congress in 1925. This activity has contributed impressively to the Music Division’s famed collection of holograph scores and – since 1940 – of world première recordings. Inevitably Spivacke’s several roles in the commissioning of new works, in arranging concerts, and in producing recordings merged when a new source of commissioning support, the McKim Fund, provided him with the opportunity to commission works, have them premièred at the Library, and underwrite a première recording in the commercial market.

Were he still with us today he probably would not have permitted a concluding word on Harold Spivacke as recording artist. Although the author knew him well in the last twenty years of his life, he never had the pleasure of hearing Dr. Spivacke play anything on a piano beyond an occasional A minor triad, for the benefit of tuning string players. Those who heard him report that his playing was accurate, sensitive, and intensely musical, fully warranting the distinction of having been a D’Albert pupil. Those reports are confirmed by a handful of recordings of short pieces by Corelli, Godard, and Schubert, and of the Lalo Symphonie Espagnole, with violinist Carolyn LeFebre, his first wife, with whom he had occasionally appeared in concert. The recordings were made on an undetermined date in the 1940’s by his beloved Recording Laboratory.

Were he still here, he would have doubtless written an entirely different article, looking to technology and the future, as a salute to his long-time friend, founder of the British Institute of Recorded Sound, Mr. Patrick Saul.

Spivacke on Sound

‘Archive of American Folk Song.’ Music Educator’s Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, Sept.-Oct. 1942.

‘The Archive of American Folk Song in the Library of Congress.’ Proceedings of the Music Teachers National Association for 1940, [Pittsburgh, Penna., 1941].

‘The Archive of American Folk Song in the Library of Congress in its relationship to the folksong collector.’ Southern Folklore Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 1, March 1938.

‘A National Archives of Sound Recording?’ Library Journal, vol. 88, no. 18, Oct. 15, 1963.

‘The place of acoustics in musicology.’ Papers Read at the Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society, December 22, 1936, Chicago, Illinois, [Oberlin, Ohio, 1937]

‘The preservation and reference services of sound recordings in a research library.’ Music Libraries and Instruments [‘Hinrichsen’s Eleventh Music Book’] London, 1961.

Ueber die objective un subjective Tonintensitӓt. Unpublished Inaugural Dissertation, University of Berlin, 1933.

Like this:

Like Loading...