Post written by Gene Baron, first presented at the 2018 ARSC Conference in Baltimore. Gene is a reitred IT professional and a lifelong Baltimorean with a background in classical percussion in musicology. You can write him at gene.baron

This is a story of how a local radio station, a man with a perfect radio voice, and a country-music loving used car dealer produced some memorable bluegrass music on radio and records in Baltimore. In the early 1970s I was a college student just north of Baltimore, and having recently developed a love for bluegrass and folk music, listened to Ray Davis on the radio and made the trip to Johnny’s to buy Wango LPs as they were issued. Davis was always happy to spend time talking about the musicians he recorded and show me the little studio where it all happened.

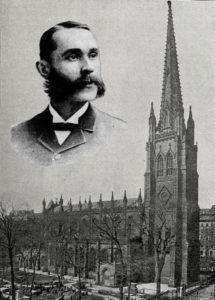

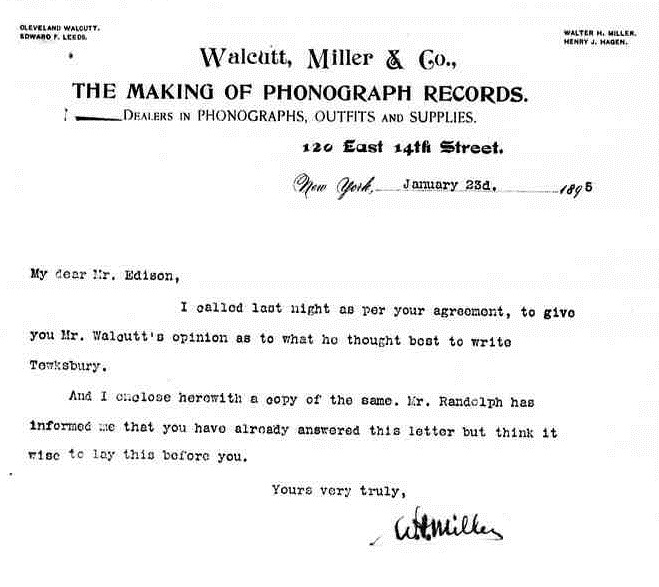

Ray Davis introduces the Stanley Brothers on the radio from Johnny’s Used Cars, Northeast Baltimore, Dec. 1963

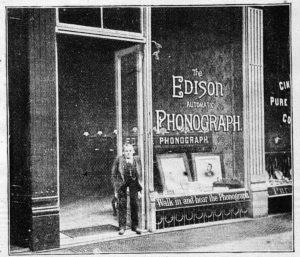

WBMD-AM went on the air in 1947. A 1,000 watt station, it shared its 750 kHz broadcast frequency with a clear channel station in Atlanta and so was limited to daylight hours. The station broadcast country music and later went to all religious programming. For many years WBMD was also the home of the Sunday afternoon shows by some of many of Baltimore’s ethnic groups, including the Italian, Greek, Irish, Jewish, Polish, German and other communities.

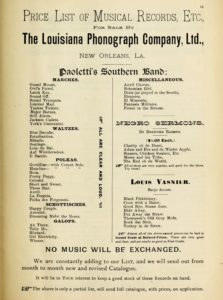

“Johnny” Wilbanks with Baltimore-based band Tex Daniels and his Lazy “H” Ranch Boys, 1951

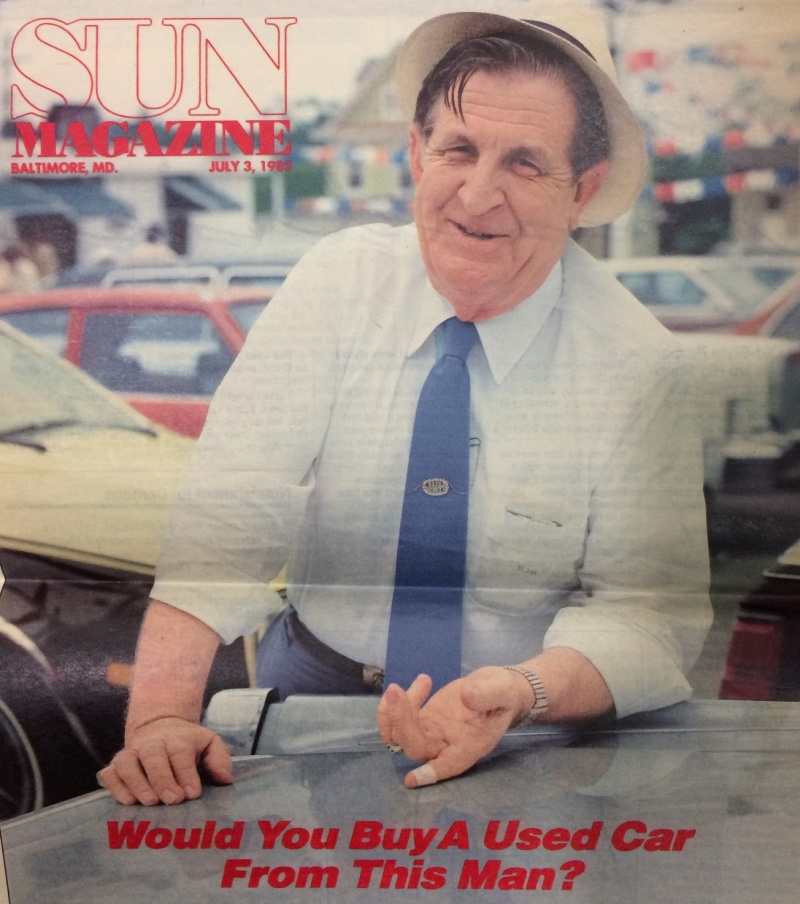

John Wilbanks came to Baltimore from his native Georgia. After suffering the loss of both legs in a railroad accident, he entered the used car business, starting Johnny’s Used Cars in downtown Baltimore, and later moved to Harford Road in the northeast part of the city. Johnny called himself “The Walking Man’s Friend”, and was unusual in that he did not haggle prices for his cars, and was known to lend people his own money to help buy a car at Johnny’s. He sometimes joked that “the quickest way to get back on your feet is to miss a few car payments.” He loved country and bluegrass music and soon sponsored bands on local radio.

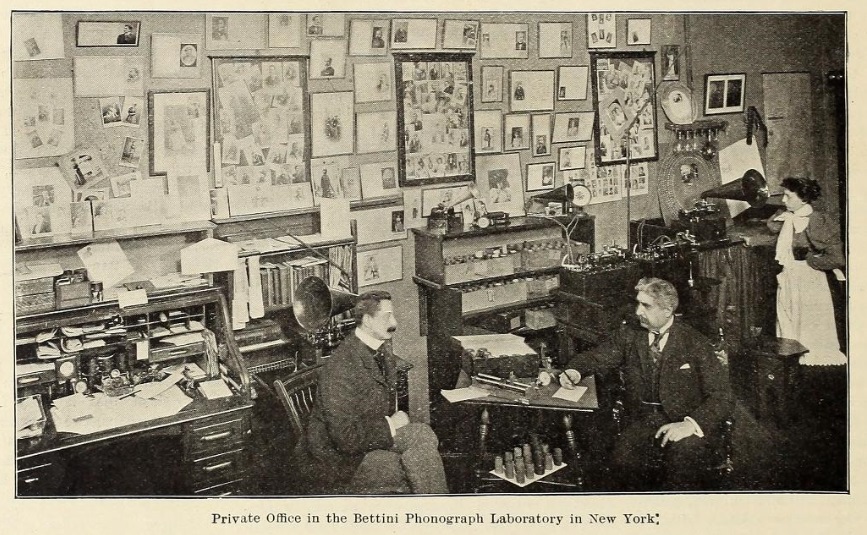

Ray Davis was born on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the small town of Wango. He started work on a radio station in Delaware at the age of 15 and remained in broadcasting for over 60 years. By the mid 1950s, he had worked on border radio and was back on the air in Baltimore. He was busy as an MC for bluegrass and country music shows in the area where he made contacts with many performers who would later play and record for him at Johnny’s or at local shows he promoted (such as NRR and Sunset Park). He was hired by Johnny and for the next 30-plus years broadcast two 15-minute radio shows on WBMD from a small studio located above the showroom. Religious music filled one of these, and later in the afternoon came more non-sacred bluegrass and country music, always with a traditional or old-time emphasis.

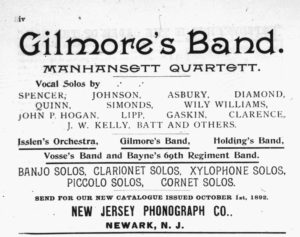

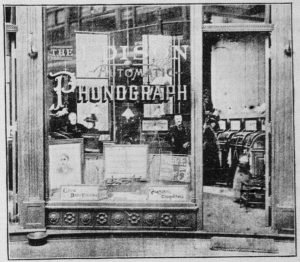

In the early 1960s Davis began issuing records on the Wango label, named after his hometown, and sold them exclusively on the air to his listening audience. What makes these records and broadcasts stand out 45 or 55 years later? For me, several reasons come to mind – much of the repertoire Davis recorded represented material not otherwise recorded by these artists, even those like the Stanley Brothers and Reno and Smiley, whose recorded output is quite extensive. We also get to hear singers and instrumentalists who did not otherwise record or perform together. Most of all I am struck by the sincerity, honesty and heartfelt nature of the records that Ray Davis made and released.

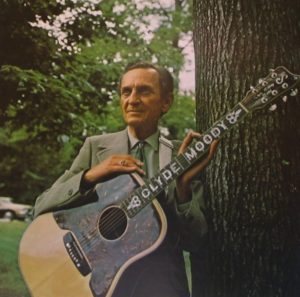

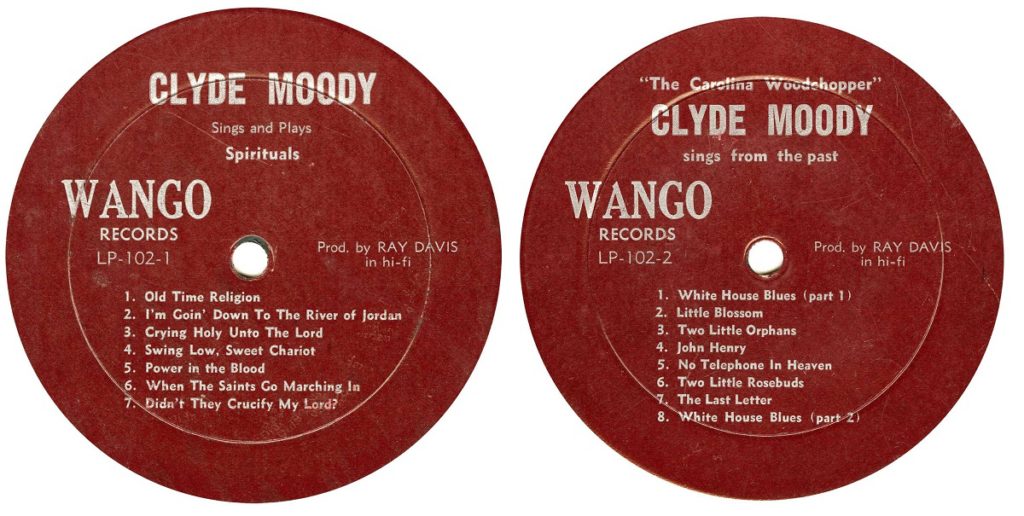

The first Wango LP that I know of featured Clyde Moody, the “Hillbilly Waltz King”, who appeared on Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys’ first recordings. After a successful career recording for King and other labels, Moody left music for a while but in 1962 he came to Baltimore and recorded an LP for Wango in the studio above Johnny’s with only his guitar, singing religious songs on one side and secular songs on the other. You can hear the strength of Moody’s voice in these songs. Here is an excerpt from that LP, Power in the Blood, a popular hymn written in the late 1800s. This LP was issued without a cover in plan white sleeve.

“Power in the Blood”, performed by Clyde Moody, issued on Wango LP 102, 1962

Labels of Moody’s Wango LP courtesy Jay Bruder

The next group to record for Ray Davis was the Stanley Brothers, with whom he had a long and close relationship. The band visited Johnny’s many times in 1963 and 1964 and recorded four LPs of music and many radio shows. The LPs were once again issued without covers in plain sleeves and Davis called the groups “John’s Gospel Quartet” and “John’s Country Quartet”, as a nod to his sponsor but also because the Stanleys were actively recording for King Records at the time. Significantly, Davis was keen to have the Stanleys record more old-time and traditional repertoire than what was featured on their most recent albums for King, and for the three gospel LPs he and Carter Stanley chose many songs from old hymnbooks. A couple of examples below of songs the Stanleys recorded only for Davis – first from an Albert E. Brumley hymnbook is Little Old Country Church House with Baltimore-based band leader Jack Cooke singing the tenor part.

The Stanley Brothers, at the time based in Florida, recorded for Wango as “John’s Gospel Quartet” and “John’s Country Quartet”

“The Little Old Country Church House”, by the Stanley Brothers (as “John’s Gospel Quartet”) with Jack Cooke. Recorded 1963 for Wango.

“Your Saddle is Empty Old Pal”, by the Stanley Brothers (as “John’s Country Quartet”)

Excerpts of Davis’ announcements, mentioning Johnny’s Used Cars and Wango Records. Other Johnny’s slogans included “working close to save you money” and “ride like a prince, pay like a pauper.”

Reno and Red Smiley parted ways because of Smiley’s health issues, but he rejoined Reno and his new partner Bill Harrell and in 1971 made some recordings for Wango not long before his death. By this time, Ray Davis was recording from his basement studio in Glen Burnie, just south of Baltimore, and was recording in stereo and including covers and notes with his albums. Here is a song from Reno and Smiley’s last sessions, “I’ve Just Got to See You Once More”, written by Little Jimmie Dickens and done in Reno and Smiley’s favored close-harmony style:

“I’ve Just Got to See You Once More”, by Reno and Smiley. Recorded 1971 for Wango.

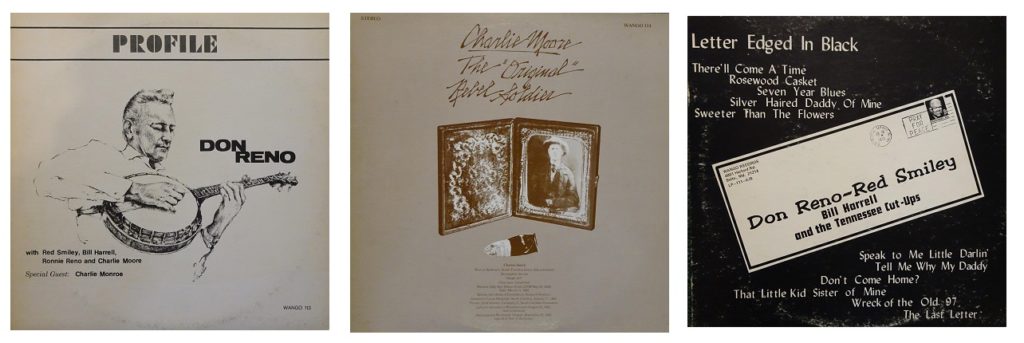

1970s Wango Records of Don Reno, Red Smiley and Charlie Moore

Charlie Moore was another favorite of Davis’s. Moore’s well-known song Legend of the Rebel Soldier was first recorded for Wango and popularized by the Country Gentlemen and others. Davis teamed Moore with Don Reno for some recordings I think are some of Moore’s best. Here with Don Reno playing lead guitar and Jimmy Arnold on banjo is Johnny Bond’s classic I Wonder Where You Are Tonight. Arnold, like many featured here and recorded by Ray Davis – such as Carter Stanley, Red Smiley, Charlie Moore and James King – died very much too young, another reason to value these recordings.

“I Wonder Where You Are Tonight”, by Charlie Moore

Another of Ray Davis’s talents should not be overlooked. He made an album of recitations with bluegrass backing which he issued only on 8-track tape in the mid-1970s. His best known, Little Orphan Joe, may be too “plum pitiful”, as Davis would say, but here is an extract of a poem from the 1920s called Touch of the Master’s Hand, with backing by Don Reno and Bill Harrell:

“Touch of the Master’s Hand”, Ray Davis with Don Reno and Bill Harrell

Activity slowed considerably for the next several years, with no releases on Wango, although some material was reissued on County and Rebel record labels. Davis continued his daily radio shows and promotion of bluegrass shows at parks and local fire halls. WBMD was acquired by the Family Radio network and still broadcasts religious music and bible discussion at 750 KHz. Johnny kept selling cars on Harford Rd. until retiring in 1996. He died in 1999 and is still fondly remembered as a Baltimore institution by many.

Johnny Wilbanks on the cover of Sun magazine, 1983

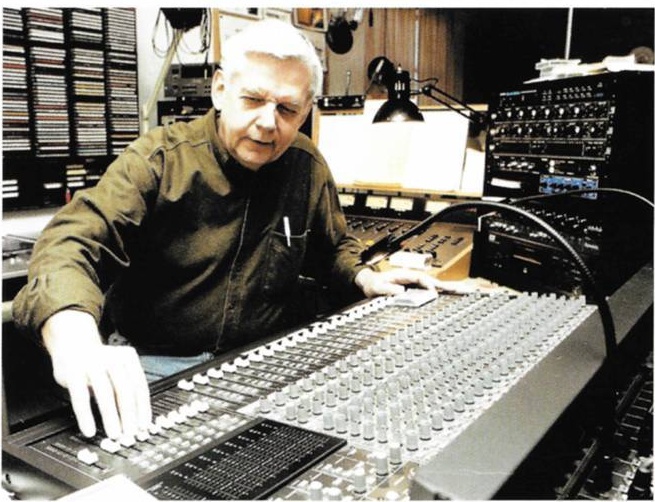

Ray Davis continued his broadcasts for Johnny’s, and in 1985 he took his smooth voice and his recordings down the road to public radio station WAMU-FM in Washington DC, where he was on the air for 28 years, moving to WAMU’s HD station and its online counterpart Bluegrass Country when most music was phased out from the schedule on the FM station. He continued to produce Wango CDs, often referring to them as the Basement Tapes, mostly to offer as premiums for fundraisers.

In addition to repackaging some of the material discussed previously, Davis promoted and recorded some of the younger generation of bluegrass artists such as James King, David Davis and the Warrior River Boys, Scott Brannon and others, always keeping that old time traditional sound that Davis preferred. Here from the late 1990s is a little of the favorite old spiritual In the Sweet By and By sung by Scott Brannon and David Davis:

“In the Sweet By and By”, by Scott Brannon and David Davis

Ray Davis was diagnosed with leukemia and ended his 60+ year radio career in September of 2013. He died a little over a year later. I hope this has shed some light on an important Baltimore bluegrass story. The Wango LPs, and even most of the reissues, are no longer in print and are now difficult to find. For the 30-some years I listened to Ray Davis on the radio, he would always close every show by solemnly proclaiming ‘It’s hymn time’, so let’s go back to the little studio above Johnny’s one more time, all the way back to 1967 and listen to Don Reno, Bill Harrell and the Tennessee Cut-Ups in another favorite four-part harmony hymn from the 19th century, Will There Be Any Stars in my Crown.

“Will There Be Any Stars in my Crown”, Wango LP 112, 1967

A

A