Post written by Mason Vander Lugt, National Recording Preservation Board / Library of Congress.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Phonograph Monthly Review was founded by Axel B. Johnson in October 1926. It was the first American magazine about the appreciation and collecting of records by enthusiasts, and helped organize a budding culture of record collectors and scholars. You can now view a full run of the magazine on Archive.org through the work of the National Recording Preservation Board.

State of the Art

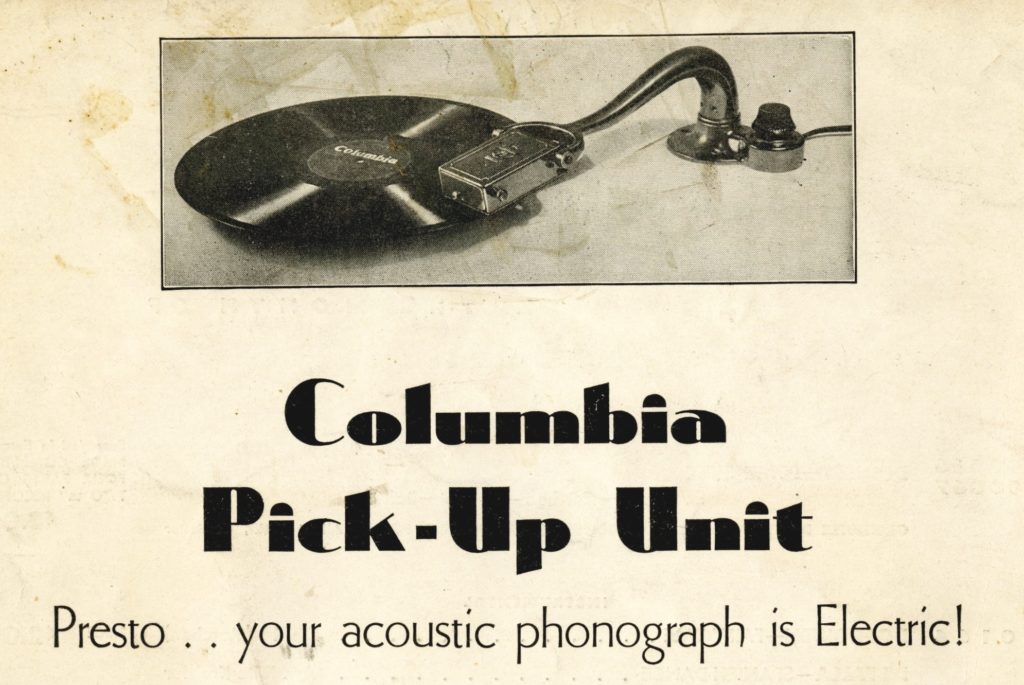

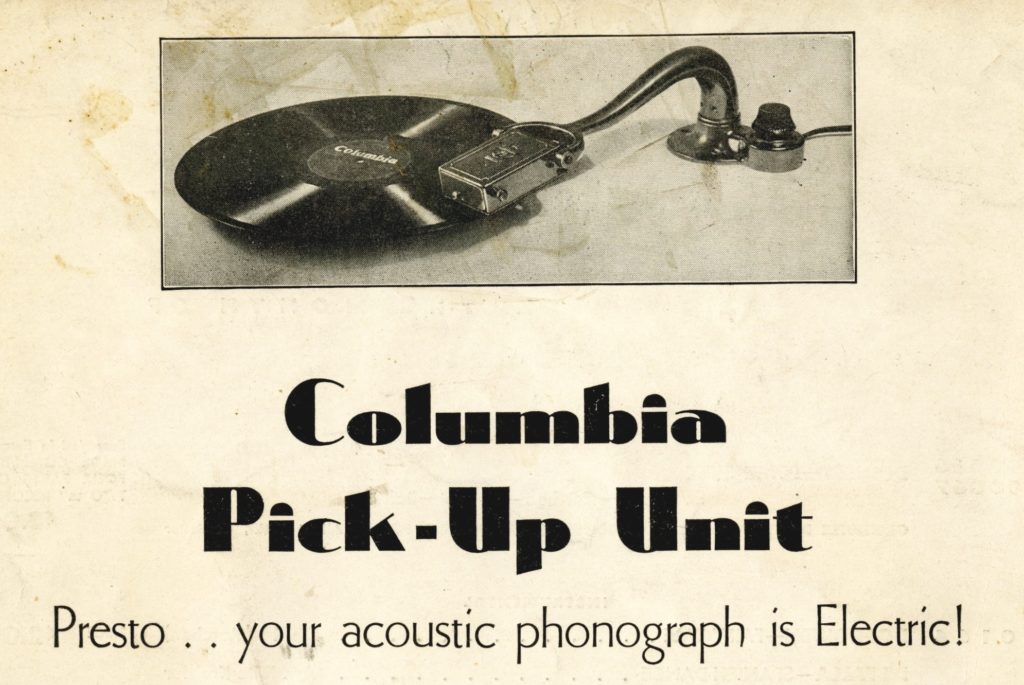

Phonograph Monthly Review (‘PMR’) was born into exciting times in the entertainment industry. Consumer radio had been on the ascent for several years, and with RCA’s formation of the NBC network in 1926, it looked ready for the first time to disrupt recording. Columbia and Victor had only the year before licensed Westrex’s electrical recording process, while Brunswick adapted General Electric’s pallophotophone system. Sometimes overlooked in the transition to electrical ‘recording’ are the equally innovative eletro-magnetic reproduction technologies, in the forms of the Brunswick Panatrope and Victor Electrola.

One of Columbia’s electrical reproduction offerings adapted users’ existing phonographs (PMR 4:11)

The improved fidelity of electrical recording and reproduction revived interest in recordings of classical music, which were somewhat shortchanged by the acoustic processes. Columbia debuted the ‘Masterworks’ line in late 1924, assembling longer works into albums (following the example of the Gramophone Co. / HMV) and presented complete symphonies, concertos, and chamber works often for the first time. Victor followed suit with the ‘Musical Masterpiece’ line in 1927, but added the innovation of automatically playing through the sides in sequence, creating the first commercially successful record changer in the form of the Automatic Orthophonic Victrola.

Columbia Masterworks Advertisement (PMR 1:3)

Creating the Collector

PMR features articles about the top orchestras and famous composers, and reviews of the most recent releases, and could have stopped there, but Johnson felt a higher purpose. He believed that through careful listening and discussion, anyone could attain a sophisticated appreciation of ‘serious’ music. The magazine staff were charter members and officers of the Boston Gramophone Society and encouraged the creation of and participation in the same.

This wasn’t an entirely new concept. PMR never concealed the fact that their model adapted the example set in England by Compton MacKenzie’s magazine Gramophone and the National Gramophonic Society (see ‘At Jethou’, 2:3 and ‘A Resumé’, 2:1). Both Gramophone and PMR aspired to be more than a magazine or a social club. In editorials, Johnson refers frequently to the ‘phonograph society movement’ or ‘phono-musical movement’, or ‘the cause’. The cause was a democratic, communal musical education, and this required a systematic study of the ‘literature’.

In ‘More Important than the Music: A History of Jazz Discography’, Bruce D. Epperson grants Gramophone the first formal discographical lists, but PMR the first freestanding discographical article, in Robert Donaldson Darrell’s ‘Dvorak’s Recorded Works’ (3:8). Darrell would go on to edit PMR and its successor Music Lover’s Guide, and would compile the influential ‘Gramophone Shop Encyclopedia of Recorded Music’ in 1935.

PMR reinforced the collaborative culture through recurring ‘Phonograph Society Reports’ and ‘Phonograph Activities’ columns, as well as a robust correspondence column for those too remote to participate in person. The ‘Mart and Exchange’ column was another innovation, allowing readers to advertise records (or literature) they were looking to buy or sell.

PMR, Gramophone, and the various societies changed the relationship between composition, performance, and recording. Before recordings, one could comment on the merits of a composition, or on the qualities imparted by a conductor or performer’s interpretation of it. Recording a work, for better or worse, allowed listeners to share a fixed reference point – still an interpretive performance of a composition, but a particular instantiation of it that could be replayed and compared. Focusing on recordings didn’t end or undermine live performance or its appreciation, but created a new intellectual space and a new kind of enthusiast – the record collector. These values and practices were expanded and codified in the 1930s and 40s in jazz magazines like Down Beat and Record Changer.

The Music

Changes in technology and culture are interesting in retrospect, but PMR’s readers subscribed for the music. 1927-1932 was a golden age in American orchestral music, with the best orchestras led by some of the most legendary conductors. Leopold Stokowski was at the helm of the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. Serge Koussevitzky led the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Willem Mengelberg and Wilhelm Furtwangler alternately conducted the New York Philharmonic, while Arturo Toscanini guest conducted (Walter Damrosch led the New York Symphony Orchestra, then separate). Richard Strauss’ recordings with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra were imported by Brunswick. PMR’s profiles, histories and discographies of these institutions were its main attraction.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The best American orchestras of the day

While PMR always focused on orchestral music, it also reviewed chamber music, instrumental solos and art songs, opera, light music, musical theater, band music, popular songs and instrumentals, dance music and foreign recordings. The reviews section reads like a ‘hall of fame’ of 20th century artists – violin by Heifetz and Kreisler, piano by Cortot, Godowsky and Paderewski. Jazz by Armstrong, Ellington and Waller. PMR didn’t explore popular artists with the depth of the composers and conductors, but included interviews with Leo Reisman (3:1) and Lee Morse (4:6), and a serial autobiography of Nat Shilkret (vol. 1).

The Recording Industry

PMR also featured articles on the recording industry past and present, like ‘How the Sounds Get Into Your Record by the Electrical Process’ (1:1), ‘Echoes from the OKeh Recording Studio’ (2:3) and ‘The First Years of the Phonograph’ (6:6). Despite frequent disdain for broadcasting among writers, PMR includes announcements that help ground recording in a wider media context, with articles like ‘The New Columbia Broadcasting System’ (1:12), ‘The Phonograph and the Sonal Film’ (4:11) and ‘Television’ (5:3). In one of PMR’s last issues, Sergei Rachmaninoff weighs in on recording vs. broadcast (6:3).

Ulysses “Jim” Walsh first published in PMR. His first article, ‘Pioneer Phonograph Advertising’ (3:6) reviews the preceding 25 years of the recording industry through print advertisements. After a pair of rambling articles titled ‘By the Way’ in 3:10-11, he writes a trio of remembrances of recording pioneers passed on – J.S. MacDonald (“Harry MacDonough”) (6:1-2), Sam H. Rous (“S.H. Dudley”) (6:4) and Anthony and Harrison (6:5). These last articles set the pattern for his prolific and influential column ‘Favorite Pioneer Recording Artists’ in Hobbies magazine.

Regular columns included ‘Record Budgets’, to assist readers in building a library without breaking the bank, ‘Phonographic Echoes’ to keep readers apprised of news, events and industry developments, and ‘British Chatter’ to keep the line open with the substantial gramophile contingent across the pond.

PMR for sale at H. Royer Smith Co., Philadelphia – ‘The World’s Record Shop’ (PMR 3:7)

PMR’s Legacy

After several years of contracting markets (records and otherwise), Phonograph Monthly Review printed its last in March 1932. The final issue begins poignantly with a memorial to John Philip Sousa, who died earlier in the same month. Johnson and Darrell went on to found the ‘Music Lover’s Guide’ magazine in New York in September 1932 which turned into ‘The American Music Lover’ (1935-1941) and ultimately ‘American Record Guide’, still publishing.

The full run of Phonograph Monthly Review can now be viewed on Archive.org, through the work of the National Recording Preservation Board. Thank you to professor, collector and antiquarian Dave Radcliffe of Blacksburg Virginia for lending the beautifully preserved complete run of the magazine that made this project possible.

Like this:

Like Loading...