Post written by Mason Vander Lugt, National Recording Preservation Board. This is the second in a series of studies of the early recording industry. Read the first about the North American Phonograph Company and Edison Phonograph Works here. The author is seeking catalogs of any other North American local subsidiaries for the third part. Please write mlug@loc.gov if you can help.

The National Recording Preservation Board is pleased to announce a discography of the cylinder recordings of the Columbia Phonograph Company 1889-1896, available now at Archive.org. Complementing Tim Gracyk’s “Cylinder Lists”, which the NRPB posted to Archive.org August of last year, this new resource completes documentation of the cylinder output of the pioneering company who “founded the record industry” in the early 1890s.

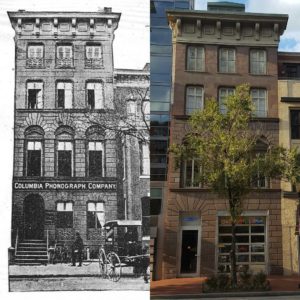

Columbia’s original headquarters at 627 E. St. NW still stand, today housing Central Liquors. Left image from Phonogram 1:3, 1891, right taken by author, 2016.

Tim Brooks’ 1978 ARSC Journal article Columbia Records in the 1890’s: Founding the Record Industry provides the authoritative story of how Columbia rose to dominate the recording industry through Edward Easton’s vision and grit (and a strategic alliance with American Graphophone). The article tells the story so well, in my opinion, that I’m going to ask that interested readers download it from the ARSC AMP database and focus here on some other aspects of the story.

Why study old catalogs?

The first point I want to address is – what’s the point of studying old catalogs for which few corresponding recordings survive? Original catalogs allow us to learn about the development of the industry through primary sources – the artists and repertoire, the breadth and depth of material and relative popularity of different genres over time.

They can also give us valuable information about the few recordings that do survive, such as those in the UCSB “Recorded Incunabula” playlists and Glenn Sage’s CDs, many of which are sourced from the Library of Congress collections. Because recording logs don’t survive and consistent permanent numbering wasn’t applied in this period, when a selection was added to or dropped from catalogs can provide a natural range for issue dates.

John Yorke Atlee and the United States Marine Band were Columbia’s main attractions in its early years. Images from Phonogram 1:8 and 1:10.

Although most of these recordings don’t survive in their original form, for reasons I’ll touch on below, we can still experience approximations of many of these through later issues. In 1895, as Columbia moved into new offices in New York City, the United States Gramophone Company began recording many of the same artists in Washington. Actor David C. Bangs, auctioneer W.O. Beckenbaugh, popular singer Maud Foster, the Brilliant Quartette, banjoists Cullen and Collins, clarinetist Felix Iardella (Jardella on Berliner) and cornetist W. Paris Chambers are among those who would record for Berliner, but not later Victor or Columbia discs.

Many performers from these catalogs recorded prolifically in the following years, and these lists provide insight into their early repertoire. Others, like George H. Diamond, Dan Kelly “Pat Brady” and Al Reeves “The Famous Banjo Comedian” were famous and/or widely recorded in this period but leave us unfortunately few or no recordings today. Similarly, much of the band and tin pan alley vocal repertoire remained popular into the disc recording era to survive to the present, but a few, like “Maggie Murphy’s home”, “Down went McGinty” and “Ta ra ra boom de ay!” were popular enough at the time to warrant parody records but faded before the more durable formats or prolific output of later generations could save contemporary performances.

Even when we can’t hear contemporary recordings, reading about what was recording can feed the imagination – whether it’s the calliope imitations of the Brilliant Quartette, descriptions of Dan Kelly’s and Russell Hunting’s skits, or the 1892 Republican campaign song “Democracy’s Going to Grass”, imagining these lost sounds may not be an academic exercise, but it can be a fun one.

Russell Hunting (as Michael Casey) and Dan Kelly (as Pat Brady) were two of the most famous recorded humorists of the early 1890s. Both began with other companies (Hunting with New England, Kelly with Ohio), and were added to Columbia’s catalogs beginning April 1893. Images from Phonogram 2:8-9 and 3:3-4.

Finally, I hope I can revive some interest in the music of this period. Within the relatively small community of people who are interested in historical American music, I find that folk music is revered as authentic and worthy of preservation and study while popular music, excepting maybe Sousa’s marches and a few great hits of tin pan alley, are ignored and forgotten. Still, sheet music remains for many works when recordings don’t. Searching Youtube reveals a few artists working in this direction, but I’d like to encourage musicians to consider reviving these (or let me know if I’m off base and this is a thing…)

Columbia’s extent and position within the industry

Just how important was Columbia compared to the North American parent company and the other sub-companies? Columbia may have been the first sub-company to institute their own recording program. The first document reproduced in the discography advertises “whistling solos by artistic whistlers” alongside recordings taken at the Edison Works. This is dated November 15, two months before Edison agreed to allow the sub-companies to manufacture their own recordings. Other companies may have been recording on a small scale for local demonstrations, or purchasing from independent recordists – every phonograph sold or leased at this time would have been capable of recording – but this Columbia advertisement is probably the first surviving documentation of the public sale of records (Edison’s would have been sold only to the sub-companies).

In these first 8 months, entertainment recordings would have been used to demonstrate the phonograph to potential business customers, or in public exhibitions, as the November ’89 pamhplet describes “At the Bull Run Panorama the Phonograph delivers lectures descriptive of the scenes there displayed”. By July 1890 Columbia had installed their first automatic phonograph, in the historic Ebbitt House Drug Store at F St. NW and 14th St. NW, only a few blocks from their headquarters at 627 E. St. NW[i]. By November, they had placed more than a hundred across the city[ii].

This quickly became the dominant model for exploiting the technology and by April of the following year, according to Phonogram, Columbia was shipping records across the country[iii]. In the same issue, Columbia began running ads boasting “we sell more records than all other dealers combined”. This might easily be dismissed as advertising rhetoric except that when Columbia’s president Edward Easton said the same at the 1892 convention of the North American sub-companies nobody challenged him. In fact – the context of the discussion was whether the other sub-companies were entitled to royalties on Columbia’s sales within their territories.

Columbia identified titles and performers on their cylinder records using a printed paper band, similar to North American’s title ring, but without requiring the special channeled rim. Photo by the author.

Why do so few survive?

If Columbia sold so prolifically, why do so few of their recordings survive to the present day? The answer is probably a combination of factors –

- The entire industry was relatively small in scale. Columbia bought less than 70,000 blanks from Edison between 1889 and 1894[iv], and some portion of these would have been resold to Columbia’s business customers for dictation. For comparison, according to Antique Phonograph Monthly, Edison sold approximately 2 million cylinder records in 1900 and 4 million in 1902. As discussed in the previous post the market for recordings outpaced supply in this period, so Columbia’s output was probably limited by their capacity to record and/or duplicate, or Edison’s ability to supply blanks.

- The format is unstable. Brown wax, designed for ease of recording rather than durability, wears easily. The Edison factory would consider a master record too worn to duplicate from after 200 plays[v]. Those that were saved might have been degraded by mold or chemical instability (efflorescence).

- They were seen more as working material than cultural record. Not that they didn’t understand this potential for the technology – both Edison and Columbia advertised the phonograph’s utility to preserve voices of family or “great artists”, and Columbia advertised some artists such as cornetist Jules Levy as great artists, but they probably regarded most of their records the way we might think today of old CDs or cassettes. If anyone at Columbia preserved special recordings like Edison did, there is no record of it.

Where’s Len?

Histories of recording pioneer Len Spencer, such as this printed in the relatively contemporary Phonoscope, usually place him virtually at the founding of the Columbia Company in January 1889, but his first appearance in these catalogs is in two undated catalogs from ca. 1895, after the company had opened a New York office and begun recording New York artists. A 1930 article by Columbia Manager Frank Dorian printed in Phonograph Monthly Review similarly suggests Spencer recorded for them “by the round” before his catalog debut[vi].

The most likely explanation is that Spencer recorded briefly in the uncredited vocal series that ran between December 1890 and January 1892 (and/or the “recitations” series, variously uncredited). A sudden drop in both series after January 1892 may corroborate this in addition to the statement in Phonoscope about his move to the United States Phonograph Company (at that time, in fact, the New Jersey Phonograph Company, another North American subsidiary) and Spencer’s headlining role in a 1892 New Jersey catalog in the Library of Congress.

Other possibilities include lost catalogs – unlikely since the found and included catalogs seem to present naturally growing and declining series – or that Spencer recorded as a kind of independent contractor, as Atlee was known to, whose records would supply the local trade but wouldn’t be distributed.

P.S. “New Paris Waltz” by E.M. Waterbury is available for adoption at the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive

Notes:

- [i] Edward D. Easton to James O. Clephane, July 8, 1890, via Edison Papers Project

- [ii] Phonogram 1:1 p. 24

- [iii] See Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of Local Phonograph Companies (pp. 53-67 original) for a discussion of the role of the automatic phonograph in the industry. Phonogram 1:4 pp. 88-92 describes Columbia’s early 1891 operations.

- [iv] Testimony of George B. Redfearn in American Graphophone vs. National Phonograph via Edison Papers Project (pages 280-282 original, images 205-206)

- [v] Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of Local Phonograph Companies p. 89 original

- [vi] See Phonograph Monthly Review Vol. 6 No. 3 for more of Dorian’s reminiscences of Columbia’s place in the early industry